Please Restore My Privacy, Dignity, and Reputation

“Privacy and ownership of information are at the core of the social graph issues. Much like there is a conflict of interest around attention information between online retailers and users, there is a mismatch between what individuals and companies want from social networks. When any social network starts, it is hungry to leverage other networks…. But as individuals, we do not care about either young or old networks. We care about ease of use and privacy.”

Alex Iskold, Read/Write Web [3]

The use of controversial membership and invitation practices by social networking site Tagged.com during the spring of 2007 exemplified the way ethical conflict affects design and highlighted how compromises in decisions that affect user experience can create unexpected ethical consequences. The brouhaha Tagged.com generated demonstrated the power of network mechanisms to serve as experience amplifiers, by affecting many interconnected people, and inspired considerable ill-will among members and non-members alike. Figure 1 shows Tagged.com.

Tagged.com is certainly not the only business venture in the crowded social networking space to experiment with questionable registration mechanisms, as the example of Quechup.com showed just a few months later. However, recounting the experiences of Tagged.com members offers good qualitative insights into ways conflicting perspectives can result in ethical challenges for UX design and [4].

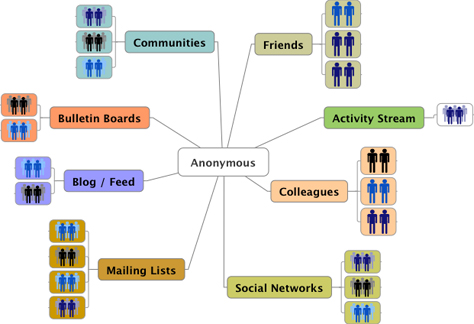

In May of 2007, along with many others, I received a flurry of email invitations, urging me to join a new social networking site called Tagged.com. Ostensibly from colleagues or friends, these invitations invariably read, “Simon has added you as a friend on Tagged. Is Simon your friend? Please respond, or Simon may think you said no.” In retrospect, it is easy to see how these invitations made a play for our emotions, relying on the natural inclination to acknowledge someone we know by name. Waves of similar pseudo-personal invitations spread rapidly, appearing in my inbox and on public and private mailing lists, as well as on corporate and public bulletin boards and community discussion forums. This phenomenon touched every area of the social Web in one way or another.

Strangely, waves of personal email messages followed the invitations from Tagged, bringing apologies and warnings from the same colleagues or friends who had ostensibly sent the original Tagged.com invitations. A growing number of bulletins advised everyone to disregard any invitation received from Tagged.com, especially those that seemed to come from a friend, and warned of proliferating spam invitations, address book harvesting, and privacy violations. The contrast between the genuinely personal warning messages, and the generic, but seemingly personal invitations was striking.

Here are some email messages that relate the experiences of UX design professionals on Tagged.com. A sample email apology from a colleague:

The following warning message, from another friend and new Tagged.com member, specifically mentions the user experience of the registration process and how it helped fool him.

Note—The emphasis is mine. The author received all email transcriptions either directly from people who registered for Tagged.com and requested anonymity or second hand from others.

How embarrassing indeed, especially since canceling a newly registered account did not stop the flood of outbound invitation emails. The experience was socially so painful, it prompted people caught up in the process to contact Tagged.com repeatedly and insist the service stop sending out invitations under their names.

This is one such cease-and-desist message, shared by another colleague who was a new Tagged.com member:

Eight hundred spammed contacts means quite a few email apologies! Yet while this was happening, Tagged.com received strong praise from leading technology and Web 2.0 media outlets for successfully recruiting so many new members in the crowded social networking marketplace. On May 9th, for example, Michael Arrington of TechCrunch wrote a brief article titled, “Tagged.com Turns Profitable—May Be Fastest Growing Social Network.” It read:

“Tagged is also very aggressive with signing up new users. At registration, users are strongly encouraged to invite their entire address book as friends. It’s a highly viral, albeit controversial, way to quickly add lots of new users.” [5]

“Aggressive,” “highly viral,” and “controversial” sound more like a new and highly contagious disease than a networking service. (And “strongly encouraged” is always an ominous choice of words when describing something supposedly voluntary and positive.)

Tagged.com did respond to some of these urgent cease-and-desist messages. This is a reply to the message above, sent by a Tagged.com customer service representative:

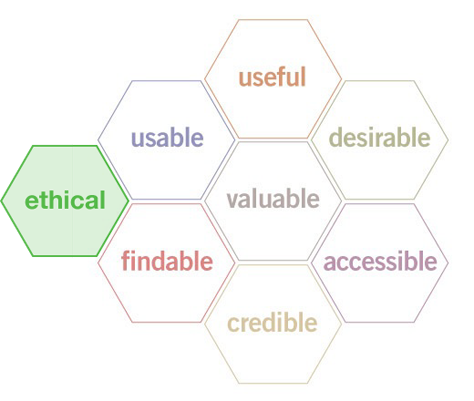

Is this an inconvenience? Or is it unethical—a violation of privacy and other rights? That depends on how you look at things.

Perspectives in Conflict

I asked friends and colleagues about the experience of registering for Tagged.com, only to realize that the service was mining their personal address books to broadcast disingenuous invitations. Responses ranged from deeply embarrassed to incensed by the damage this caused to delicate and valuable social networks, as you can see in the following examples.

Here’s an excerpt from another message:

In the case of Tagged.com, one might easily have forgiven a few misdirected invitations, but 800 indiscriminate solicitations could amount to considerable damage to one’s professional and personal social networks. In addition to privacy violations—who wants their contact information shared involuntarily—there were the costs of public and private embarrassment, possible damage to one’s professional and personal reputations, and unknown future costs from lost opportunities.

Changing the scale from the individual to the group level, we can see that many of these contacts were posting addresses for mailing lists, bulletin boards, communities, or forums. The amplifying nature of network mechanisms—the ripple effect—meant literally thousands of people were affected each time an invitation went out. The ripple effect changed the quality of the damage to the collective social fabric as well as increasing the number of people affected. The perceived value of a mailing list, community, or forum that is subject to spamming declines very quickly, as anyone with a clogged inbox knows. (Recognizing this, list administrators for groups affected by Tagged.com reacted quickly to invitations from Quechup.com, issuing warnings right away.)

However, Tagged.com saw the results of its design decisions regarding its registration process as largely positive—at least initially—from a business perspective. Tagged.com benefited from rapidly growing membership and activity rolls; increases in usage, traffic, and exposure; lowered customer acquisition costs; potential profitability; perceived advantages versus current or potential competitors; and positive endorsement from influential media. For startups with unproven business models and value propositions, these sorts of accomplishments represent steps toward validation and legitimacy and often serve as the essential criteria for financial and business survival. Under these circumstances, the temptations to accelerate growth by cutting ethical corners can be profound.

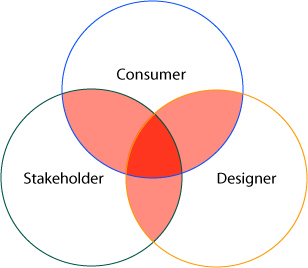

In retrospect, it is easy to see that, in those instances where customer and community needs—such as the value and importance of preserving privacy, voluntary disclosure of information, and respect for the nuances and boundaries of complex, real-life relationships—came into conflict with business pressures to register new members quickly and gather intelligence about their social networks by capturing their social graphs, Tagged.com decided to favor the business agenda and sacrifice ethical integrity by designing an effective harvesting experience.