Small Screens

Some ways of coping with small screens include

- prioritizing features and content

- reducing levels of hierarchy for content

- communicating workflows

Prioritizing Features and Content

Current Web design best practices and guidelines assume a 1024x768 screen resolution. For smartphones, the most popular screen resolution is 320x480. Therefore, it’s usually necessary to sacrifice some of a Web site’s features and content when designing a mobile version of the site, so users can easily find the ones they really need. You must give priority to the tasks and content users are most likely to use on a mobile device.

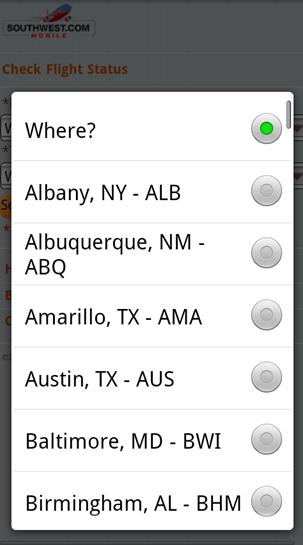

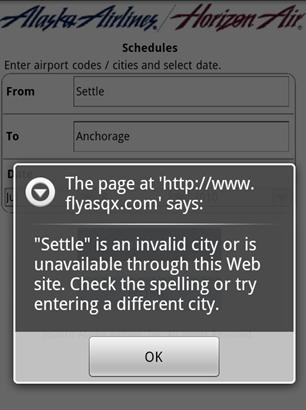

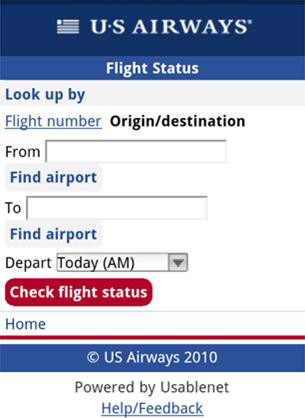

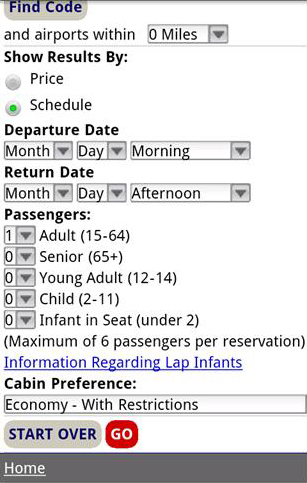

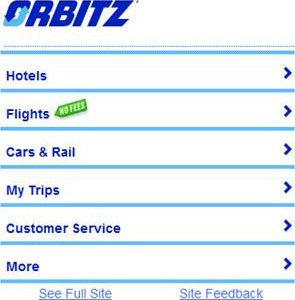

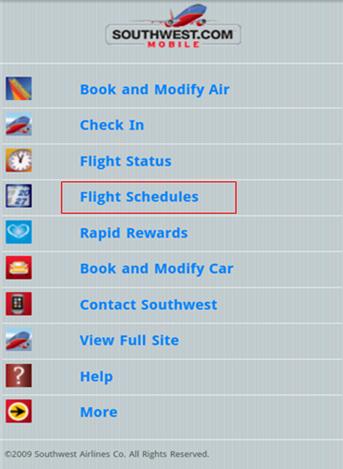

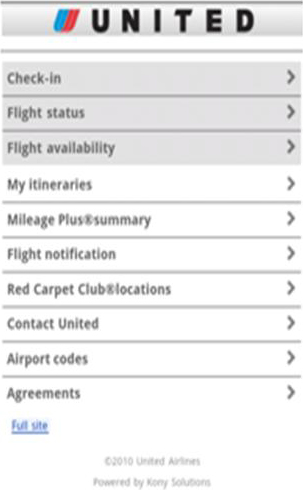

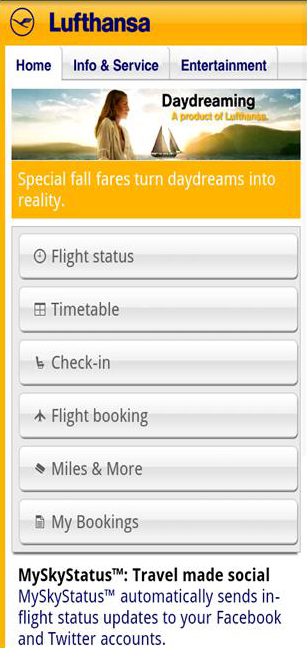

Let’s look at some examples of the differences between mobile Web sites and the corresponding sites on a computer. On the majority of the home pages for airlines’ mobile Web sites, there are fewer than ten features, or functions, available. The tasks they most frequently support are checking in for a flight and checking flight status, as Figures 1 and 2 show.

The Amazon mobile home page lists only four departments, as shown in Figure 3, rather than all of the departments on the Amazon Web site.

In Figure 4, the YouTube mobile Web site shows only four of the current day’s spotlight videos on its home page, unlike the home page on its Web site, which lists not only spotlight videos, but also videos people are watching now, featured videos, and the most popular videos.

Reducing Levels of Hierarchy for Content

In his discussion of complexity versus simplicity on UX Magazine, Francisco Inchauste talks about the difference between things being “adjacent in space” and “stacked in time.” Content that is adjacent in space appears adjacent on the same screen. Content that is stacked in time appears sequentially, when users click links to view different screens—that is, in a step-by-step manner. Inchauste says achieving balance between these two modes of information presentation is desirable when designing Web pages for computers, but especially so when designing for the small screens of mobile devices.

In comparison to designing a Web site’s structure, it’s necessary to flatten the structure of a mobile site and reduce its levels of hierarchy to ensure visitors don’t get lost. For example, on an ecommerce Web site, users might have to go through the following steps to view a product description: home page > products > product category > product description. In contrast, on a mobile ecommerce site, one way to reduce the levels of hierarchy is displaying important product categories on the home page. As Figure 5 shows, the Best Buy mobile Web site lists the most frequently visited product categories on its home page—for example, TV & Video, Audio, Car & GPS, Cameras & Camcorders, and Computers.

Communicating Workflows

It’s always important to avoid confusing users by making them go through too many steps to accomplish what they want to do. But, on mobile devices, it’s sometimes more efficient to display additional information on a new screen instead of putting all of the information on the same screen. Take booking an airline ticket as an example. When users search for flights, they get a list of results from which they can select flights. Users usually need to select both a departing flight and a returning flight. On a Web site, selection of both legs of a trip can appear on the same page. Some airlines like Lufthansa, as shown in Figure 6, divide the search results page into two columns, with departing flights in the column on the left and returning flights in the column on the right. It’s clear to users that they need to select a flight in each column to book round-trip flights.

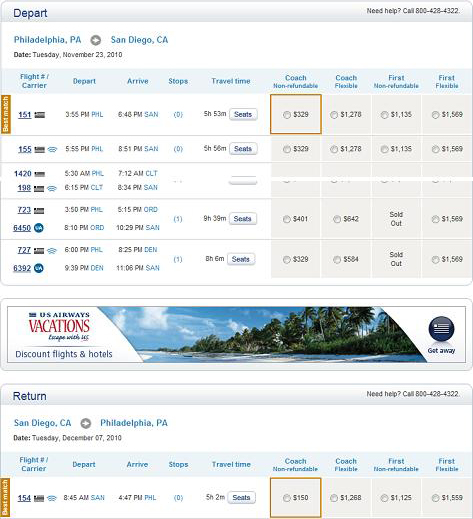

Other airlines, like US Airways and Southwest, instead display a long page of results, listing returning flights after departing flights. To remind users they should select an option from both groups, there is usually a clear separation between the two groups of flights, as shown in Figure 7. Both Lufthansa and US Airways display departing and returning flights in close proximity.

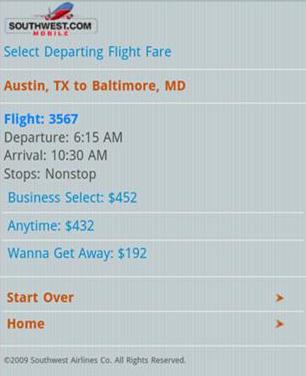

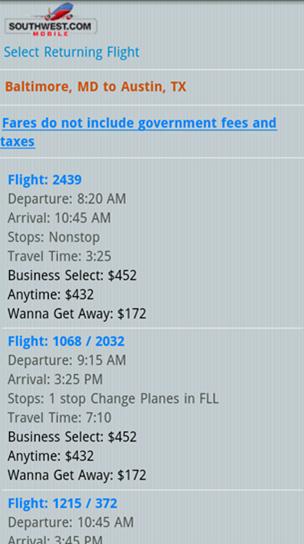

However, mobile Web pages would become extremely long if both legs of a trip were to appear one after another on the same page, and dividing a page into two columns is almost impossible. Therefore, most airlines have adopted this best practice: The two legs of a trip should appear on two separate screens—that is, stacked in time, as Figures 8 and 9 show. Once users finish selecting their departing flight, returning flights appear on a subsequent page.

One important thing to keep in mind is that users need to be given an explicit indication when they transit from the departing-flight page to the returning-flight page; otherwise, they might become confused when they see two pages that look very similar without knowing why. There are several ways to make this transition clear and explicit, so users realize they are now on a different page. For example, the Southwest mobile Web site prominently displays the headings Select Departing Flight Fare and Select Returning Flight. Displaying these headings in a bigger font size or a different color would make them even more prominent. Using a button or link with an explicit label, such as Select Return Flight, instead of an implicit label like Next would also be helpful.