Plugging Gaps in Your Search Engine’s Index

It’s a dirty little secret that search engines don’t always index all the content they’re supposed to. The problem isn’t with the software itself. Rather, it’s due to the engine simply not knowing about content areas that exist on a given site. And the engine may not know because it’s likely that you don’t. If your site is actually a large set of subsites—typical of many enterprise-scale Web environments—then it’s simply hard to know what content is out there.

One solution is to analyze your top queries with zero results. Of those, identify which aren’t retrieving results because there simply is no content to match searchers’ needs.

Then look at those queries as a group. First, are you surprised by what you find? Do you see any patterns, anything in common at all? Would you have expected there to be content to match those queries? If so, who would have created it, and in what unit would they likely work?

You’re mostly there, Holmes; now go talk to someone in that part of your organization. Find out if there is, indeed, content that needs to be crawled in order to match these null queries (and if not, to make a gentle recommendation that it should be created).

Making Query Entry Easier by Fixing “the Box”

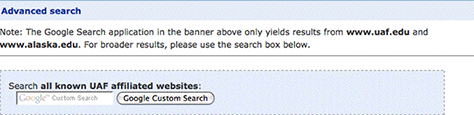

Most sites these days happily sport “the box,” a simple text-entry box (and an accompanying “search” button) that persists on every page in a fixed position (see Figure 1). It’s a life preserver of sorts—searchers know exactly where to look for it when they need to execute a search, and it works the same way wherever they find it.

If you have “the box” in place throughout your site, congratulations! But have you considered how wide it should be? It had better be wide enough to accommodate the majority of your queries. SSA will help you figure out how long your queries typically run, so you can plan your design of the text-entry box accordingly.

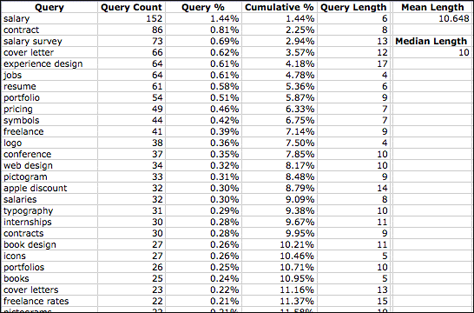

In this example, I analyzed AIGA’s top 500 unique queries for a specific month—these accounted for exactly 37% of all search activity (see Figure 2). I used Microsoft’s “LEN” function to count the number of characters in each query and then calculated the queries’ mean and median lengths (10.648 and 10, respectively).

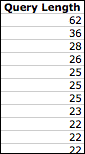

After I sorted by query length, you can see that the maximum length among these 500 queries was 62 characters, but that is something of an outlier; the next longest was 36, then 28, and then it flattened out (apparently, Zipf is everywhere), as shown in Figure 3.

Based on this data, I might be safe using a search entry box with a width in the 15–20 character range. If horizontal real estate isn’t at a premium, a width of 30 characters would be even better.

I could take my analysis further and compare a sample from the long tail and see if query length differs greatly. Still, with this small sample, I’m safely addressing our most frequent queries and almost 40% of all search activity.

Accommodating Strange Query Syntax

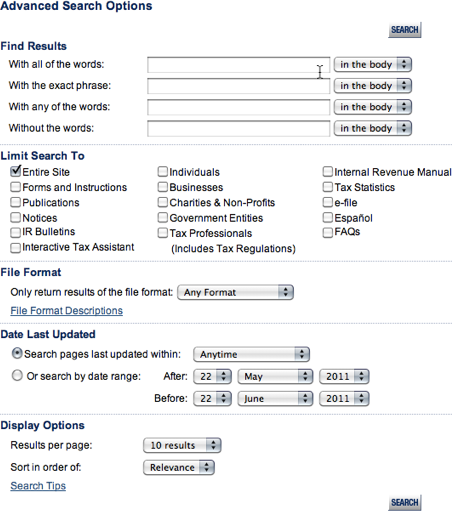

Once upon a time, prior to the advent of the Web, most online searching was done in either library catalogs or commercial databases that were hugely expensive to use (think hundreds of dollars by the hour) and usually horribly designed. Accordingly, searchers in those days were more than casual and definitely not lazy. They were quite motivated to learn all sorts of search tricks, like using Boolean operators (for example, OR, AND, and NOT), wildcards, ways to truncate terms, and lots of other weirdness.

These days, Google is good enough that most searchers can be lazy, entering a term or two, and expecting something reasonably good in return. Still, there are a few holdouts, and if your site is older or tends to be used by researchers or librarians, there’s a good chance that you may need to consider supporting old-style query syntax.

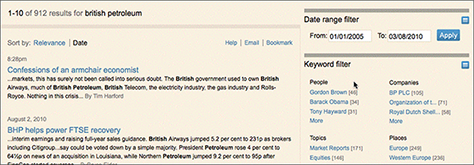

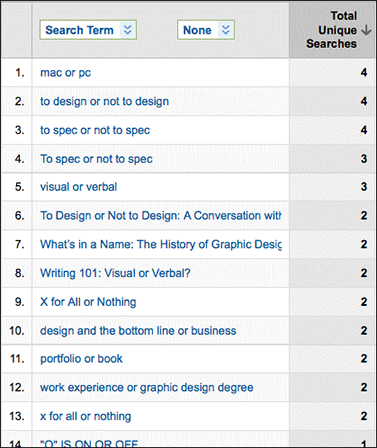

A simple way to check is to search your queries for such instances. In the example below, I used Google Analytics to filter a year’s worth of AIGA.org queries for the operator OR (see Figure 4). Of the over 75,000 unique queries for the entire year, only 121 unique queries (and 142 searches overall) included OR. And most of those queries were not using OR as a Boolean operator.

The use of AND, however, was a bit more common; it was included in 1,596 unique queries and 2,205 searches overall. (NOT showed up in 84 unique queries and 112 searches overall.) But out of over 75,000 unique queries and 188,000 searches overall, the volume of searching using Boolean queries is still quite small—in the 1%–2% range—and the majority of those queries don’t use AND, OR, and NOT as Boolean operators. So AIGA is probably safe in not supporting Boolean operators in its query syntax.

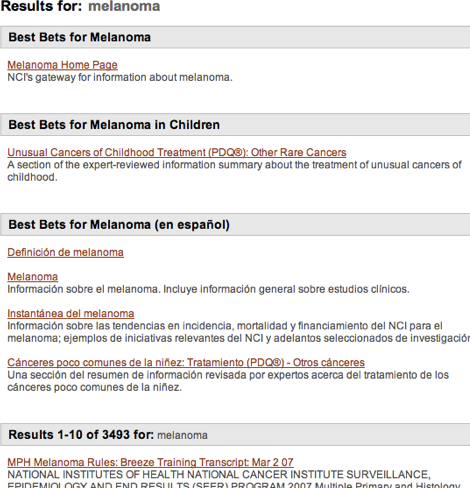

Determining What Your Best Bets Should Be

Best bets (aka “recommended links”) are simple. They’re search results that have been manually connected to a particular query. Why do this? Because search engines are robots, and robots aren’t always that effective at retrieving good search results.

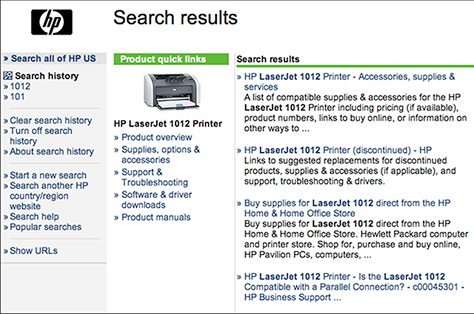

In the example in Figure 5, the National Cancer Institute wanted to make sure that searchers always retrieved something useful when searching for melanoma. The organization manually attached three sets of best bet search results to the query, and these are displayed before the search engine’s automated results show up.

So, while best bets are simple, they’re also powerful. “Powerful” in the sense that they can really improve the search experience. And “powerful” in that they can be a weapon wielded in your organization’s political battles.

For example, who gets to determine which are the most appropriate best bets for a query? If, for example, your organization sells hardware products, and someone searches for a product’s name, should there be a best bet result from marketing? Or from sales? Or from the tech support department? Whose should be the highest priority? This sort of situation can spin out into a political firefight very quickly.

And who gets to determine which queries merit best bets in the first place? (And how many should there be at most? We’ve not seen this addressed by researchers, but three or four seems plenty, since you don’t want to completely obstruct the raw search results.)

Rather than let best bets become a political headache, use data—query data—to quell or at least blunt these battles. Look to the short head for common queries, and look at them longitudinally to determine which are the most persistent over time. The combination of popularity and persistence is a great driver for choosing queries that merit best bets.

If you do have multiple best bet candidates, consider prioritizing them by determining the relative importance of a particular query to different audience segments. Consider our hardware vendor once more: if the people searching a specific product name are three times more likely to be existing customers seeking to download drivers, rather than prospects who might be looking to learn about a product, then the data would suggest that tech support’s best bet should come first. Argument settled.

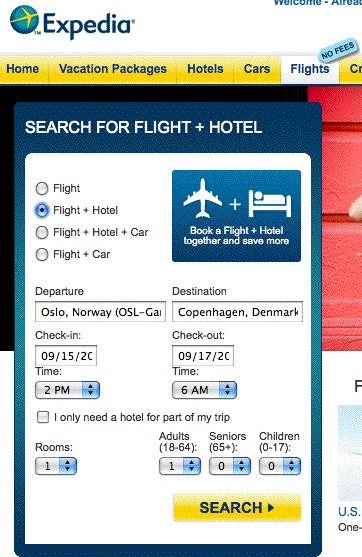

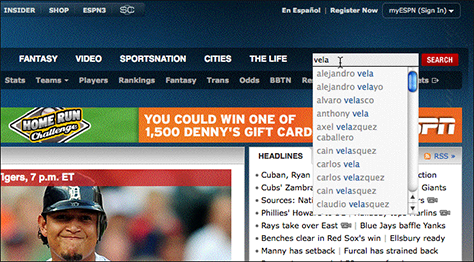

Helping Searchers Auto-Complete Their Queries

Unless you’ve been under a rock for the past few years, you’ve likely encountered sites that automatically complete your queries (also known as “type-ahead”). In effect, the search engine has been given enough information to predict what you want to search—or, at least, provide you with a few useful possibilities for you to select from. Auto-completion can help searchers save time entering a query. They can just click or tab over to their selection, rather than continue typing. And if they’re not exactly sure how to enter their query—perhaps they don’t know the proper spelling of a term—auto-completion will expose some useful possibilities.

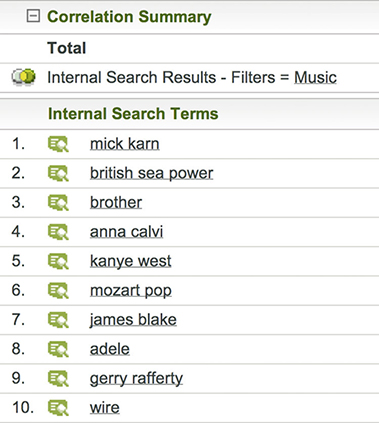

Where does SSA fit in auto-completion? Well, it might be tempting to simply use all of your queries—or even your most frequent queries—as your auto-completion list, but beware: these queries are likely to be quite dirty in all senses. They’ll include typos, irrelevant terms, and terms that are dirty in the pornographic sense.

Rather than using raw queries, rely on a cleaned-up version. For example, you may already have a list of keywords associated with best bet search results. Given that they’re probably based on your frequent queries and that they’ve been scrubbed, they’re a great starting point. You might also consider using a tool that can perform entity extraction on your queries to give you a set of proper nouns for your auto-completion list. But again, you’ll still need to manually review such a list; no software application will be able to do that as well as you can.

SSA can also help you identify metadata attributes and content types. Consider them candidates for items to add to an auto-completion list. You may find that you can go out and acquire certain metadata—say, place names—from commercial sources and insert them directly into your auto-completion list. (Just make sure that your newly added terms have content associated with them, or they’ll be navigational dead-ends.) Or you may already have the terms you need somewhere inside your organization.

For example, ESPN.com enables searchers to type ahead and retrieve names of professional athletes, as shown in Figure 6.

Improving a “No Results Found” Page

Whoever issued the click that led to the following page in Figure 7 should be reported to the authorities immediately. Bad user!

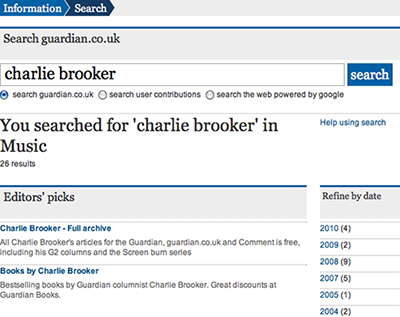

We’ve all seen error messages like these before. Some are unhelpful (see Figure 7), while others seem to go out of their way to make you feel like a lunkhead. Many sites are addressing their messaging of their “file not found” pages, moving from 404-impersonality to a more helpful approach that suggests alternatives.

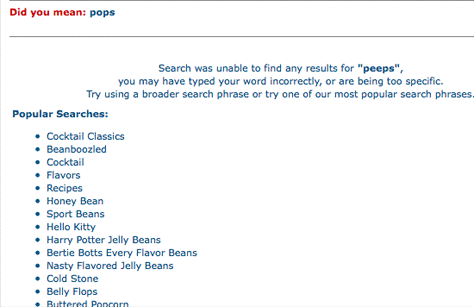

Similarly, there’s no reason not to go beyond default “results not found” pages and do even better. And SSA can help in a very simple way, as shown in Figure 8.

Certainly, JellyBelly.com’s copy could be even a tad bit more helpful. But more importantly, the company realizes that, in the context of a failed search, it’s a good idea to suggest other queries to try. These suggestions are frequent queries; even better would be suggesting queries with synonyms for the failed query term. (But let’s face it: there probably are no synonyms for “peeps.”) Either way, the searcher is now just one click away from more search results, rather than being made to feel like an idiot.