Cognitive Fluency

In previous columns, I’ve talked about how sensitive people are to the work of decision making. Even though it may be at a subconscious level, people are affected by how easy or difficult it is to think about something. Not surprisingly, it turns out that people prefer things that are easy to think about rather than things that are difficult to think about. This feeling of ease or difficulty is known as cognitive fluency. Cognitive fluency refers to the subjective experience of the ease or difficulty of completing a mental task. It refers not to the mental process itself, but rather the feeling people associate with the process.

Fluency is important because of its power and influence over how we think about things and exerts its power in primarily two ways: its subtlety and its pervasiveness. Fluency guides our thinking in situations where we have no idea that it is at work, and it affects us in any situation where we weigh information. The full force of its power comes from the fact that we often misattribute the sensation of ease or difficulty in thinking about something to the thing itself.

Familiarity

To learn more about how fluency works, let’s start by looking at some research in this area. Some of the earliest research occurred in the 1960s, when Robert Zajonc conducted a series of experiments in which he found that the more people were exposed to certain words, patterns, or images of faces, the more they liked them. Zajonc’s experiments uncovered what we now know as the Mere Exposure Effect—the finding that the number of times people are exposed to certain stimuli positively influences their preferences for those stimuli.

This is an interesting finding because, along with more recent research, it reveals that the feeling of familiarity has a strong influence over what types of things people find attractive. In another series of studies, researchers found that, when they asked people to choose the most appealing face in a group of faces, people tended to select those that were composites of all the others. Psychologists call this the Beauty-in-Averageness Effect.

This research reveals that familiarity is a strong motivator of human behavior. In general, people like things that are familiar because they don’t require as much mental work as things that are new and different do. Familiarity is attractive because familiar things require only limited cognitive resources and feel easy.

The Familiarity / Fluency Link

Because familiarity enables easy mental processing, it feels fluent. So people often equate the feeling of fluency with familiarity. That is, people often infer familiarity when a stimulus feels easy to process. Thus, fluency becomes a common mental shortcut that people use to quickly determine whether a particular stimulus is something they’ve encountered before. Most of the time, this shortcut works well. We don’t need to expend time and mental effort scrutinizing something anew if we’ve already made this mental effort when we previously encountered it.

Sometimes, however, this mental shortcut can lead us astray—especially because there are many things that influence the feeling of fluency. Let’s look at some research that reveals some subtle aspects of information display that influence cognitive processing.

In one study, researchers presented participants with the names of hypothetical food additives and asked them to judge how harmful they might be. People perceived additives with names that were hard to pronounce as being more harmful than those with names that were easier to pronounce. On a subconscious level, people were equating ease or difficulty of pronunciation with an assumption about familiarity. When the pronunciation seemed easy, people assumed it was because they’d previously encountered the additive and had already done the mental work of processing information about it. Since it seemed familiar, they assumed it was safe.

The opposite was true of additives that were difficult to pronounce. The disfluency of a name’s harder pronunciation made an additive seem more foreign, and therefore, worthy of a more wary approach. These findings show that even ease of pronunciation, an aspect of cognitive fluency, by itself can influence perceptions of risk. [1]

Fonts and Cognitive Fluency

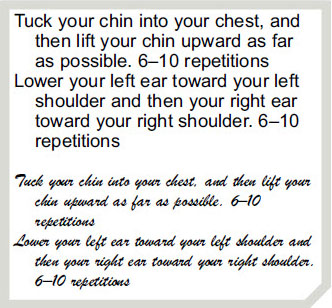

Ease of pronunciation is just one of many aspects of cognitive fluency. In a different study, researchers asked participants to read instructions on how to do an exercise routine. As Figure 1 shows, they presented the instructions in two different fonts—a font that was easy to read and a font that was more difficult to read.

When they asked participants to estimate how long it would take to actually perform the exercise routine, people anticipated that it would take almost twice as long to do the exercise when reading instructions in the font that was difficult to read, in comparison to the font that was easier to read. In the first example, people estimated it would take about 8 minutes to perform the exercise, while in the second example, they estimated it would take about 15 minutes. With the font that was easy to read, they also assumed that the exercise routine would flow more naturally and were, therefore, more willing to incorporate it into their daily activities. [1]

In this study, people were actually transferring the difficulty of reading the instructions onto the task itself! This demonstrates the power of fluency and how it can affect people’s judgment and motivation regarding the adoption of new behaviors. If you want people to adopt new behaviors or perceive something new as being easy, it’s important to consider how the information about it appears in print.

In another study, researchers asked people to choose between two phones. They presented information about the phones in either a font that was easy to read or a font that was more difficult to read. Researchers found that the type of font affected people’s willingness to make a decision. While only 17% of the participants postponed the decision when they received information in the font that was easy to read, 41% did so when the font was difficult to read. Subconsciously, people attributed the difficulty of reading the information as a cue that the decision itself was difficult to make. [2]