Jeff: I sort of mark my career in two phases: one before the blog and one after the blog. Before the blog, I had a background as a programmer, working with a lot of small businesses.

I’d been attracted to programming at a very young age, on early personal computers. I had a Commodore 64, an Amiga, an Apple II. Once I learned to bend the machine to my will, I sort of fell in love with that idea and followed it through. That led me to the realization that I loved this stuff a little too much. I really liked it! It wasn’t really a job to me. It was kind of a lifestyle, almost, and the blog was an offshoot of that. I wanted to talk to people about my stuff and my job.

I’d switched to a large pharmaceutical company at that point. I was happy, but I didn’t have people who loved this stuff as much as I did. So, starting a blog was a way to reach out and touch the rest of the world and talk about stuff I love. You see who finds your blog, and the world kind of beats a path to your door. I reached a point in my career where I found I loved this stuff so much that I wanted to move somewhere and work for a company where software is the product—where we’re not just plumbers connecting pipes together, we’re the thing driving revenue for the company.

Peter: Coding is quite an ephemeral thing. What is the thing that really grabs you? Is it the thrill of solving a problem?

Jeff: Well, to be honest, it’s that you get to play God. You get to create a world where you control everything that happens. And beyond that, in the sense of playing God, it’s also kind of cool that you can actually create a world. People create whole online worlds for games—panoramas of forests, trees, and houses and people to interact with. I just found that fascinating—that there’s this world inside the world, and it’s kind of the ultimate machine. Certainly, as a kid, I tried to take things apart and build things. I remember trying to build an arcade machine out of cardboard, because I loved arcade games. And cardboard is great, but cardboard is kind of a pain in the butt compared to software. Software is very malleable building stuff, and you can build anything in it if you’re prepared to deal with the fact you’re building a virtual thing and not a physical thing. So, I think that’s seductive and what drew me to it the most.

Peter: So, you’d gotten as far as moving to a pharmaceutical company, what happened then?

Jeff: Yes, and I wanted to make a transition to a company where the software was the actual product, not a side effect of doing business that they tolerated and paid for—like hiring a plumber. I wanted to be part of the revenue stream for the company.

So, I moved to California, which is like a Mecca for geeks, because the personal computer was born here. Consider all of the companies in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was nice to come to Mecca, if you will, where a lot of stuff originally happened. There’s a huge tech industry here, of course.

I took a job at a small company that did consulting work for Microsoft, a boutique consulting firm called Vertigo Software. And during that time, the blog got ridiculously popular. The blog was a factor in my being hired at Vertigo, because the CEO liked my blog. He’s a nice guy and still a close friend. So, while I was at Vertigo the blog really took off and started to overshadow my regular work. It started to seem very quaint to come into work and influence 10, 20, or, if I was lucky, 50 people in a day, when I could write a blog entry and influence tens of thousands of people in a day. So it started to be a sort of Clark Kent / Superman dichotomy.

Peter: A lot of passion comes out in your blog. Was there ever any conflict between the job and the blog?

Jeff: No, the company that I worked for was very tolerant of the blogging. In fact, I also had a blog at Vertigo. But it’s hard to get people to maintain a blog. It was a good working relationship. Anyway, what it came down to was that I had this big ball of energy in the blog, and it was a question of: What do you want to do with this big ball of energy? Are you just going to throw it away? Are you going to let it dissipate? Are you going to push it in a direction? What do you do when you have a big ball of energy?

I thought it would be irresponsible not to take that ball of energy and push it in a direction that made something? That’s when I started reaching out to people online to try and find out what to do with it. And one of the people I contacted was Joel Spolsky, who became my business partner for Stack Overflow. At the time, Experts Exchange was very popular in Google search results and had the answers for a lot of technical questions, but it was not a pleasant experience. So Joel’s idea—and it was a very good idea—was, “Lets do Experts Exchange, but without all the unpleasantness attached to it.”

Peter: I love the idea of the ball of energy. It’s like a video game where you’ve built up enough energy to do a special move, and you’re just deciding which special move to do.

Jeff: That’s right! That’s a great way to explain it!

Peter: I’m not familiar with Experts Exchange. How did that work?

Jeff: I wouldn’t say Experts Exchange is defunct, but they don’t show up in search results as much anymore. They’ve been pretty much displaced by Stack Overflow and Stack Exchange, with recent Google algorithm changes. And that was kind of intentional, because we liked Experts Exchange in terms of the service they provided, but we felt it was like being sold a used car by the stereotypical used car salesman, trying to trick you into buying a load of things you don’t want.

Peter: Was it kind of a paid, subscription model?

Jeff: Well, they wouldn’t really show you the solution. It was printed in Klingon, so it looked like the solution wasn’t there, but it actually was. You’d type your question into the search engine and get an Experts Exchange page that said, “Oh, here’s a question almost exactly like yours!” but the answer is gibberish—unless you pay money. The problem is: you can’t do that and be a valid search engine target. It’s called cloaking when you present one set of search results to Google and another set to users. But if you scrolled all the way down, past the Klingon, the answer was actually there. But, in a lot of circles, this made them loathed.

Peter: You talk a lot about human factors on your blog. Did your interest start when you were looking at Experts Exchange or before then? You talk a lot about the human element of software engineering on the blog.

Jeff: I do because, if you get down to first causes, it’s not actually a problem with the way software is constructed; it’s a disconnect between what the programmers or designers thought should be happening and what the users think should be happening.

When you actually examine software development itself, usually a lot of the problems are around what we call peopleware. Problems like: Why isn’t it working? Why are we so far behind schedule? Why can nobody work together on this team? It’s not because they didn’t have the right compilers.

The book Peopleware was actually instrumental in our getting this understanding that 80% of anything you attack is about questions like: How do people interact with the software? How can you get them to interact in a way that makes sense? That’s what you need to worry about. A lot of the time it doesn’t matter if your code is technically correct or pretty. That’s irrelevant if no one can actually understand what the hell it does. So, let’s get to first principles, first causes. Let’s understand what’s going on here. And that is: Why can’t Joe figure out your program?

The UX book that I read first and that I recommend to everybody is Don’t Make Me Think!” I have a bunch of books on my reading list about usability and human factors. I was a big Tufte fan for a long, long time, but the Krug book was really instrumental in my realizing that a lot of the stuff we worry about as programmers doesn't really matter. As a programmer, I wanted to build things that people used—that were functional and useful to people. If you analyze root causes, it’s almost always people factors that matter—usability and design play a heavy part in that.

Peter: One of the books you mention on your blog is Alan Cooper’s The Inmates Are Running the Asylum. When I read the book, I must admit to being a little bit offended by his description of software engineers as loving complexity.

Jeff: But they totally do! The book is completely correct! That’s one of my lessons to my fellow programmers: Stop trying to be a great programmer, and focus on trying to be a great human being. How do you build things that human beings can actually use. I’m not saying you have to fall in love with your fellow human beings—they’re a lot harder to love and are a lot more erratic than you’d like. But you have to appreciate that, if you want people to use your stuff, you have to understand human factors. You have to appreciate that you need to ask: What’s the prior art on this? How are other people doing this, from a design perspective? That's absolutely critical to being a great programmer.

You have to ask real people—or even better, observe them. People will tell you they’re using your application when they’re not actually using it! People can’t usually remember what they do. There’s this whole other field of data-driven ways of making things, which I’m not a huge fan of, but it’s better than guessing. Do you want to measure what your users are doing, or do you want to guess what your users are doing? Measurement is better that guessing, but it’s not the whole story.

Peter: Stack Exchange has a lot of mechanics that work really well—game mechanics like trophies, scores, only being able to vote a certain number of times each day, a question being worth less than an answer. You look at it, and it just works. How did it get to that point?

Jeff: Well, when we sat down to build it, the first thing was to figure out that we were building a Q&A system. We started looking at forums, but then realized that a Q&A system is not a forum—it’s a different beast. So, I looked at every Q&A system that was out there already, and there were a lot. It was like there was this whole underbelly of the Web that was based on Q&A that was very popular—Ask.com, Answerbag. Some very large sites were built around Q&A, and that was a good sign that the Q&A model seems to work. It’s very direct.

To be a good designer, you have to be a very good observer—and to some extent a good researcher. What have people tried before? What didn’t quite work? Don’t just look at the popular things that are working. Look at the experiments, things that didn’t work, and think about why they didn’t work. See if there was some aspect of it that did work, but some flaw that kept it from working well. There are a lot of really good ideas that are buried in some kind of related failure, but people throw away the whole thing. I think that's a mistake.

What we did—certainly what I did when I was building Stack Overflow—was to build a Frankenstein monster of stuff, of body parts from other sites that I liked. I liked this arm, this eye, this leg. I would take apart sites and discover that I really liked one part—but the rest, not so much. I was trying to build this Frankenstein monster out of just the good stuff, leaving the not-so-good stuff on the operating table.

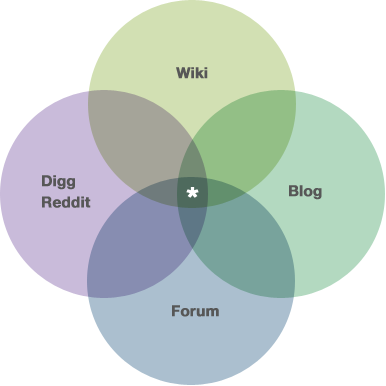

Just research everything you can on a topic—all the things that people have tried. It’s a very holistic examination of why something is working. If you go to any of the About pages on Stack Exchange sites, you’ll see a Venn diagram showing the main influences on Stack Exchange. (See Figure 1.)

I mentioned blogging earlier—and that’s an amazing way of getting information to the world—and how hard it is to get people blogging. One way to blog is to do it in fun-size blocks of work. Don’t just sit there thinking, What should I blog about? You’ll get analysis paralysis.

If you go to Q&A sites, you’ll see that there are all these people asking questions, and you might think, Hey! I know the answer to that question! or I have a comment I can provide there. So, already you’ve taken away the problem of not being able to think what to write, and you actually have a directed goal.

This isn’t like Wikipedia, which is an ownerless system. If you write an amazing entry on Wikipedia, you can’t put it on your resume. I like the editing aspect of that site, but I don’t like the ownerless aspect. We felt that, if people own stuff, they’ll take care of it. Just like if it’s your car, you’re going to keep it clean. But if it’s a rental car, who cares—it’s someone else’s problem. You want a sense of ownership, so people care about what they write. They’re open to people helping with it, but it’s their thing.

And then, of course, I thought the achievements model of the Xbox 360 was amazing—in terms of getting people to learn without reading a manual. Nobody reads a manual for a game. Having to read a manual would be ridiculous. If you bought a copy of Halo 4 tomorrow, would you go home, get out your smoking pipe, and read the manual for a day before you played the game? No, you’d pop the game in and start playing. So, the first level of the game is the tutorial. It doesn’t say, “This is the tutorial,” because that would be boring. It says, “You’ve just dropped in on a planet, but luckily there’s nobody nearby. Oh, look, you’ve found a plasma rifle. I wonder what you could do with that? Oh, look, there’s a little rock outcropping. How can I get under that? Maybe I can duck.” But it doesn’t say, “This is the tutorial.”