I started my career like any other 22-year-old, fresh out of college, with no idea of what I actually wanted to do. I had obtained my degree in Management Information Systems from the University of Connecticut School of Business, then landed a job as a Java programmer at a large insurance company. While there, I built applications that our insurance agents would use to sell our products. Not very interesting. But, as I now look back on my time working there, I recall that the company had just implemented a new team that kept interrupting my work and driving me crazy. This was the usability team.

When I was almost finished coding, these people would come to me to tell me that what I was building wasn’t easy to use. “What do they mean that it has to be easy to use?” I thought to myself. “What does that have to do with anything as long as my code works?” Needless to say, this was a constant struggle for me. I wanted to listen to them—regardless of how many times they came to me too late and gave me zero rationale to show me that their advice was valuable.

While, sometimes, my boss forced me to listen to them, many times he did not. We saw following their advice as optional—and why shouldn’t it have been? I didn’t even know why they existed or how they could make my product better! Of course, now I look back on this time and chuckle. Nevertheless, I have always kept in mind the communication gap between myself and that usability team. I’ve often thought to myself over the years, “Why didn’t I see their value back then?”

Several years later, I’d left my work as a back-end programmer and found myself doing something called information architecture (IA). I loved the work that I was doing. And, after doing some reading on Jakob Nielsen’s site, I finally understood the massive amount of revenue that usability, or ease of use, could muster on its own—without even considering all the other UX stuff. I realized why those usability people were so darn important. Why couldn’t they have explained their value to me in this way then?

In 2007, after just one year in my new IA role and when I was only 24, my boss approached me to take on the biggest project that the company—a Fortune 200 Financial Services firm—had ever taken on. He made me the lead Information Architect for a 4500-page, 12-million-dollar redesign project. It would be my job to coordinate Information Architects, Visual Designers, and Front-end Developers to deliver a brand new information architecture for the site. Yes, 4500 pages—and a look and feel that would work in any browser and support 6 million users a day.

It was during this time that I began having meetings with some pretty important people in the company, and I found myself having to explain, time and time again:

- Why this redesign was even happening

- Why it was taking so long

- What effect it would have on the status quo

After some time trying, unsuccessfully, to demonstrate the usefulness of the project, using the terms that I’d learned—“It will create a better user experience”—I found myself needing to try another tack. It seemed that no one outside User Experience understood the value that a new user experience could bring. Sure, the stakeholders all knew they needed a “good UX,” but none of them realized what that really meant. Of course, they wanted our users to be happy, but what they really wanted was to understand how this massive project that was disrupting every system in the company would affect the company’s bottom line. That was the context in which I had to start showing that a better user experience was better for everyone.

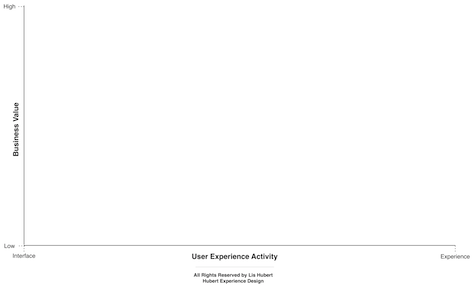

It’s now years later, and I work as an Independent UX Consultant in New York City. Over the years that it has taken to get me to this point in my career, I have realized that, despite our having a surfeit of everyday jargon, UX professionals don’t have an effective way of packaging our services that articulates our actual value to stakeholders. As someone who constantly has to show the value of what I do to get hired, I’ve seen that, even though we have lots of tools in our toolkit, no one outside our industry really gets the value of each of our tools, no matter how much we talk about them.

Basically, UX professionals are really good at coming up with various processes and tools that can help them to solve problems. But we are not so good at packaging our toolkit as a service that meets our customers’—that is, our stakeholders’—needs. Further, because we haven’t packaged our profession as a service, our stakeholders, clients, and teammates outside User Experience just don’t get that what we do goes way beyond boxes and arrows.

What’s even more interesting is that many other professions do have a concrete way of showing the value of their work. For example, agile developers have packaged what they do as a service that gets code out faster and cheaper, while maintaining good quality. Talk about concrete. Of course, there are lots of other tools in the agile toolkit, but when agile developers describe the value of agile methods, this is the way they do it—and with great success! While UX professionals create personas, scenarios, and journey maps—that sounds expensive—what does all of this really provide to a company? What is the service that we offer? What is our value?