As a point of reference, I‘ll discuss my own compass for information architecture, which I developed as part of my research for the DSIA Research Initiative. While the ideals that we’ll review won’t be foreign to many of you, recognizing these simple principles as a professional compass that benefits the organizations that we serve, might be a new idea for you. First, let’s look at the greater good.

Aligning with Business Value

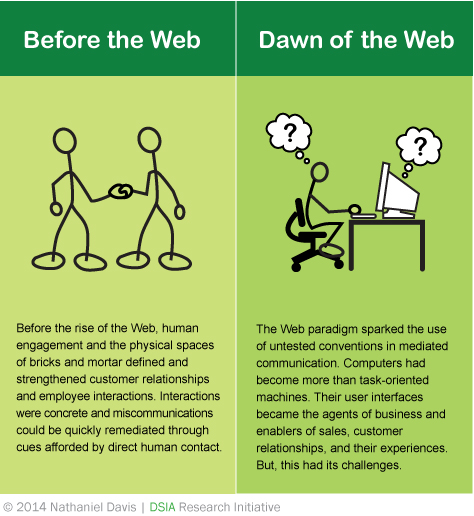

Prior to the commercialization of the Internet, companies maintained successful business relationships primarily through a great deal of personal interaction. In fact, if it weren’t for the Web, service design might have become legitimized much sooner instead of evolving to what it is today by riding the wave of the UX design movement. In the ’90s, the rapid ascendance of the Web quickly displaced what was then a rising awareness of the competitive advantage a company could gain by providing a heightened level of customer service and memorable experiences in physical spaces. Instead, the focus shifted to how people interact with each other in the then new digital space. The Web would introduce businesses and hundreds of millions of people to the nascent science of nurturing customer relationships and employee productivity through mediated communications, as represented in Figure 1.

It is important to understand that business leaders and operational decision makers think in terms of performance, functions, and tasks. These are the quantifiable chunks of any business’s operations that collectively represent the underlying context of a business.

Despite companies’ general lack of understanding of mediated communication, their deepening commitment to the Web as a primary touchpoint for commercial and operational engagement was an outcome of the measurable financial gains and operational improvements that they associated with Web technology. By allowing commerce to take place anywhere and at any time, the Web was reshaping time and space. The rewards for doing business on the Internet seemed far greater than the risks—at least until the hype and the rush to use Web technology settled down. But today, conventional wisdom about the Web has repeatedly proven that the risks actually threaten the rewards.

At the epicenter of risk and reward is a user interface (UI) engagement that focuses on information in some form of consumable or interactive content. By the end of the ’90s, there was a lot of information on the Web. Now, after the Web’s almost two decades of existence, there is a whole lot of it! And, from the evolving science of mediated communication, we know that poorly managed information threatens to undermine the effectiveness of user interfaces that relate to revenue generation and operational functions. This is where the practice of information architecture adds business value.

The immediate value proposition of information architecture centers on the way it addresses the challenges of computer-mediated exchanges of information between people and computing devices. But never mention this to a business stakeholder. Rather, when you’re given an opportunity to express the value proposition of information architecture to stakeholders, I recommend that you tell them the function of information architecture:

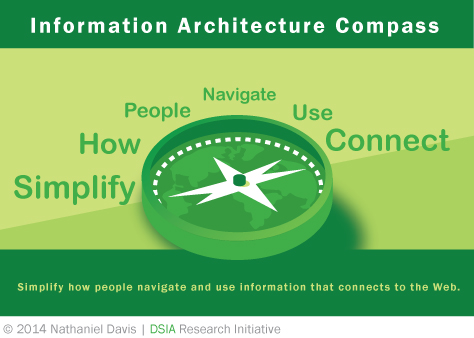

“To simplify how people navigate and use information that connects to the Web.”—The DSIA Research Initiative

If this sounds like an oversimplification of IA practice, it is. This statement focuses on how information architecture addresses two frustrating user experiences to which most people working with Web-based user interfaces can relate:

- Complex information spaces that make finding information difficult

- Poor affordances that make using information difficult or ambiguous

In this age of big and little data, information anxiety, and the exponential propagation of information on the Web, the practice of information architecture is the leading discipline seeking practical solutions and strategies for simplifying the way people navigate and use information that connects to the Web.

This statement reflects my professional compass for information architecture and is the way I communicate the role of information architecture to nontechnical audiences.

In the remainder of this column, I’ll briefly describe the principles of my IA compass, shown in Figure 2. I hope this helps you in developing and applying your own information architecture compass as you engage in future IA activities. When you use your IA compass in your work, you’ll be contributing to a greater good that builds business and organizational value.

Simplify

Push for an intuitive solution.

Focusing on simplicity always improves the act of creating an information architecture. Simplicity often correlates to relevance and is congruent with intuitiveness. When you think you’ve finished your information architecture, challenge yourself to make your solution even simpler. Consider the importance of abstraction. Abstraction is a central technique of information architecture. It promotes scalability and reuse. These are crucial concepts that resonate with organizations that have complex information technology (IT) and enterprise architectures.