Setting the context for his talk and the entire conference, Nathan first defined strategy, borrowing Wikipedia’s definition:

“A high level plan to achieve one or more goals under conditions of uncertainty. Strategy is also about attaining and maintaining a position of advantage over adversaries through the successive exploitation of known or emergent possibilities rather than committing to any specific fixed plan designed at the outset.”

Nathan looked at strategy from several different perspectives. He quoted Henry Mintzberg of McGill University who defines strategy as “a pattern in a stream of decisions.” He also described the role of strategic management in business as follows, highlighting some key phrases:

“Strategic management analyzes the major initiative taken by a company’s top management on behalf of owners, involving resources and performance in internal and external environments. It entails specifying the organization’s mission, vision, and objectives; developing policies and plans, often in terms of projects and programs, which are designed to achieve these objectives; and then allocating resources to implement the policies and plans, projects and programs. A balanced scorecard is often used to evaluate the overall performance of the business and its progress towards objectives.”

“When you ask for budget, relate each line item back to a line item in the strategy,” recommended Nathan. “Strategy is worthless unless you can act on it.” He defined strategy as “a high-level plan for action” and noted that Charles Eames defined design as “a plan for action.” Nathan believes, “Strategy is about context; the experience. It’s not about the product. It’s not about the features.”

Next, Nathan spent some time contrasting tactics, which are about “operational effectiveness and productivity,” and strategy, which focuses on “intent, goals, mission, vision, and culture.” Usability is a tactic; an experience realizes a strategy.

- Tactics—How can we make, deliver, and support the best products possible? What features should we offer?

- Strategy—“What business should we be in? What should we make or offer? Why?”

“User experience is important to strategy,” stated Nathan, showing several examples of how experience creates value—for example, phones connected to landlines versus mobile phones—a market that has grown exponentially since 2000.

Nathan next spoke about some strategy tools that can help a business get to clarity:

- SWOT analysis—“This is where you are now. Where you’re strong and others are weak—that’s a strength. Where you’re weak and others are strong—that’s a weakness. Threats and opportunities are the things you should focus on now. Capitalize on your strengths and fix your weaknesses.” Figure 2 shows an example of a SWOT analysis.

- environmental analysis—This form of strategic analysis looks at

- social issues—customer needs and wants. Customers seek clarity.

- political issues—legal, regulations

- technology issues—technology trends and opportunities. Customers are afraid of technology.

- economic issues—market trends and opportunities

- industry-specific issues—whatever they might be

- competitive analysis—Discover your biggest strengths versus your competitors’ biggest weaknesses and your biggest weaknesses versus your competitors’ biggest strengths.

- positioning statement—Here is Nathan’s template for a positioning statement:

“For <target customers> that <need / care about>, our <product / service / company> is a solution that <benefit>. Unlike <our competitor>, our <product / service / company> is <unique differentiator>.”

When defining a strategy, where should you start? Nathan offered a series of questions that you can ask to help you determine the right strategy:

- “Who is your customer really?

- What is their life like, what do they need, what do they want?

- What value is being provided to them, and what kind of value can you realistically provide?

- How can you differentiate yourself based on this value?

- What’s it going to take to be successful?

- Are you ready? Is it worth doing?

- Do you have the right people. Who do you really need? Do you have the right culture?”

“Price and performance are usually what business is taught to focus on, but this isn’t how people choose products,” said Nathan.

In speaking about the relationship of business to strategy, Nathan told us: “Relationships happen in experiences.” Experiences deliver value as follows:

- "Functional Value +

- Financial Value +

- Emotional Value +

- Identity Value +

- Meaningful Value =

- TOTAL VALUE

- Functional Value +

- Financial Value =

- TOTAL QUANTITATIVE VALUE

- Emotional Value +

- Identity Value +

- Meaningful Value =

- TOTAL QUALITATIVE VALUE”

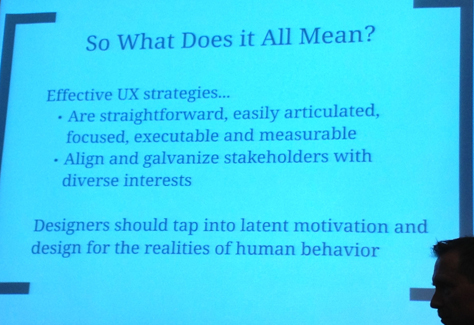

In wrapping up his presentation, shown in Figure 3, “Nathan shared the following takeaways:

- “Qualitative and quantitative; not qualitative versus quantitative.

- Strategy is derived from research.

- UX can—and should—play a role in strategy.

- Leadership is communicating vision.

- Relationships and value are built through experience.”

UX STRAT 2013: Nathan Shedroff, “What It Means to be Strategic” on SlideShare

A great Q&A followed Nathan’s presentation. Here are some of Nathan’s responses to the audience’s questions:

- Regis McKenna published the best article about Crush Marketing in the ’90s.

- “You need to marry the qualitative with the quantitative. This won’t tell us what to do, but it better informs us so we can decide what to do. We can’t be afraid of data and analysis. We have to use that lens. We can’t be afraid of data, which a lot of designers are.”

- “The best thing is to tell stories. When you find out something that isn’t part of market research, tell the story. Help them to see the qualitative in their own lives.”

- “It’s not about cheap. Every time you see a brand, that’s qualitative. Values and identity playing a role in decision making”

- About SWOT analysis: “The most important thing is to back it up with research data.”

- “No business person wants to walk away from money.”

- What companies are using UX strategy? “Apple does no testing or research. Jobs micromanaged everything.” Proctor and Gamble use quantitative data, “but make room for the qualitative. Car companies do this intuitively—design, price points. There aren’t a lot of companies doing this historically. Microsoft does more user research than anyone on the planet, but it doesn’t affect engineering decisions at a high level. Intuit is starting to do it. Maybe Nike. AutoDesk is trying to do it.”

- Question: “Often, strategy is told in the form of a presentation. What make the best presentations?” Answer: “The best presentations are well-told stories. Most presentations put you to sleep with numbers. They’re poor visually. Telling a story of what’s going on in a company. This is one of our strategic goals and why.”

- Comment: “I’ve heard that you have to go out and do your own research and should not trust market research.” Response: “You don’t have to have a huge sample. If there’s no research and you can talk to six people, talk to six people. Doing any research is better than doing none. Try the laddering technique.” (Reviewer’s note: See Michael Hawley’s column “Laddering: A Research Interview Technique for Uncovering Core Values,” on UXmatters.) “People don’t know the truth of their own behavior. If we can get marketing to do good marketing research, we can pair it with good qualitative research. Consider other things, not just obvious things. Make the case for getting more research.”

Beyond Wireframes: How UX Methods Can Foster Innovation and Solve Business Problems

Reviewer: Pabini Gabriel-Petit

Presenter: Aline Baeck

Aline Baeck, shown in Figure 4, is currently Lead User Experience Designer, Global Products, at eBay. She gave a great presentation on fostering innovation and solving business problems using UX methods that was based on her work with the Design Innovation Team at Intuit, where she was an Experience Design Architect.

Aline opened her talk with the rhetorical question: “Why innovation workshops?” and answered her question by sharing a couple of testimonials:

- “I applied the methods the next day with my team and we’ve redirected our project in a more purposeful manner…. A higher level of success is inevitable.”

- “Participants are now more effective with their teams…. We now have a shared view of what success looks like.”

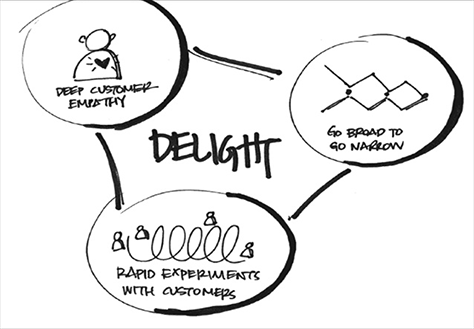

The goal of Intuit’s Design Innovation Team was to “Design for delight and get something into users’ hands as quickly as possible,” said Aline, as shown in Figure 5.

Aline told us that the team had a Eureka moment when they realized that they needed to “get design thinking into the strategy of what should be built. Intuit’s products weren’t as innovative as promised during the initial phases [of product development].” The team asked, “What’s happening that crushes innovation? How is success being measured?” Design and development cycles weren’t giving them much time, and the way they were measuring success was not supporting innovation. Product Management drove development, and we realized that “it’s about the quality of the experience.”

“What was pivotal in identifying the work that we needed to do was partnering with the Product Managers (PMs) who define the product that gets built. [With them,] we identified opportunities to increase innovation. We interviewed PMs to find out their challenges, how they felt, and their level of knowledge about design initiatives.”

The outcome was a series of innovation workshops titled “The Innovator’s Toolbox—Everyday D4D (Design for Delight) for the PM community.” The team held these workshops at the beginning of projects to discover how PMs “could leverage the way designers think,” said Aline. There were some “core differences in this workshop from others that we had done.” Our goals were to:

- Come up with “15 to 20 methods that we could leverage everyday.”

- “Facilitate the use of these methods on teams … to make decisions by leveraging the way designers think.”

There was “a single PM on a team consisting of [multiple] designers and developers and little opportunity to interact with other PMs.”

Each workshop lasted one and a half days:

- “Day 1—Solving problems with design methods

- “Day 2—Leading a team using design methods.” A cross-functional team worked together, which was a new experience for them.

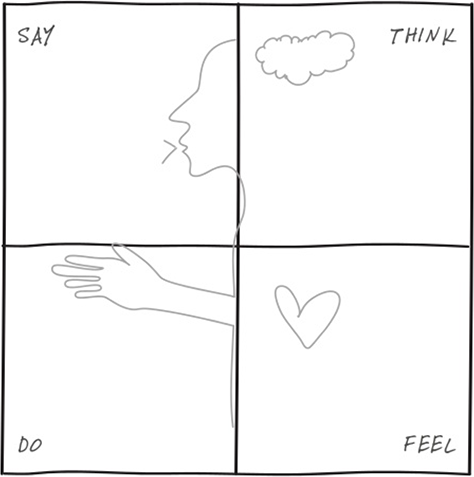

During the workshops, participants created four-quadrant empathy maps like that shown in Figure 6, to help them to “think about what we’ve learned when talking with customers and try to understand the emotional aspect of customers.”

In an empathy map, the information on the left side is explicit, while that on the right side is implicit. Teams tend to gather a lot of explicit information when interviewing customers.

Aline recommends incorporating the following core elements that were responsible for the workshops’ success:

- personalization—Personalize the workshops for each team, providing a unique workshop experience rather than running the same workshop over and over again. “One or two weeks before each workshop, interview the team about their challenges, then customize the workshop’s content to meet those challenges.”

- solving real problems—“Don’t use sample exercises. Pick problems that would feel relevant to participants—problems that you could at least partially solve by the end of the workshop—so you’re working on things they care about.” Check in with a team before a workshop to ensure that they haven’t already solved a problem. Particular PMs own problems, while others work on solving them. You can involve a client in a workshop to get their real input while working on a problem set.

- station rotation—Workshops generally include 15 people overall. Get a big room, and divide the workshop into teams of five people, at three stations. Divide the workshop’s day into three time chunks, then rotate people through the stations—except the Product Owner, who is the facilitator and always stays with the same team. Assign a problem to each team. The advantage of this approach is that participants get to experience different facilitators’ approaches to using different methods. Participants move fairly frequently between different problems. For example, a participant might spend two hours at one station, then go to a new station, where he’d get a briefing from the Product Owner on the problem the team is solving, what has transpired so far, and the methods they’re using to solve the problem. If you encounter any difficulty working with a team, it’s comforting to know that you’ll soon be rotated away from that team.

- flexible content—Based on what you’ve learned from the interviews, you’ll start Day 1 with methods that your team’s facilitator thinks appropriate, then play it by ear from there. A facilitator can use the think-aloud protocol to verbalize the decisions that he or she is making, creating a more open dialogue. This exposes participants to the underlying thinking of the facilitator and helps them to understand and learn various methods. Use methods only as long as they’re useful. If desired, you can transition methods that you’ve already picked up on Day 1 to Day 2. At the end of the first day, discuss which methods you’ve found most useful and want to take forward to Day 2—and which you want to discard or should enhance for use on Day 2. As a group, decide what the content of Day 2 should be. Day 2 is only a half day, so you should restrict the number of methods to only three or four.

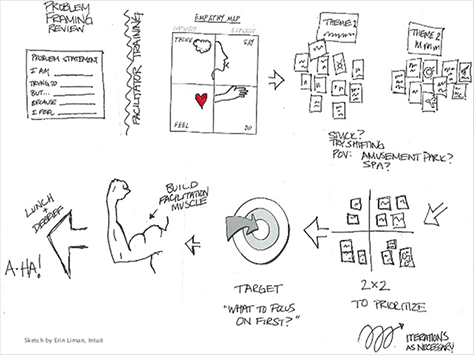

- longitudinal support—If you want to facilitate ongoing change after the workshop, assign one of workshop facilitators to support the team on an ongoing basis. When teams encounter resistance or time pressures, they may revert back to their usual ways of doing things. At Intuit, the teams created sketches on method cards that showed how the workshop had progressed, what methods they had actually used, and what the workshop had covered, similar to that shown in Figure 7. This helped them to review the workshop and build good habits. Longitudinal support really made a difference.

There were also some challenges that the Design Innovation Team encountered—but these things got better over time as they did more workshops. Deciding who they should convince to do these workshops was initially a huge barrier. They first reached out to management and got a positive response, but no workshops got scheduled. They reached out to their peers—people who were having problems and feeling the pain. Leaders knew about the pain, but weren’t actually feeling it. They reached out to product management. Personal relationships helped them to get people interested. It was also helpful to think about who would benefit from the workshops. Once the Design Innovation Team had held a few workshops, people started reaching out to them.

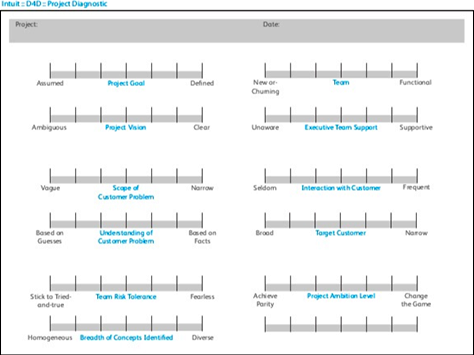

Aline shared the Diagnosis Tool that the team used to evaluate projects, shown in Figure 8. Taking five minutes to get people’s gut reaction to how they were doing on these scales raised issues that they might not otherwise have thought about.

Check out Aline’s presentation in Figure 9. I love the sketches that she included in her presentation.

UX STRAT 2013: Aline Baeck, “Beyond Wireframes: How User Experience Methods Can Foster Innovation and Solve Business Problems” on SlideShare

During the very lively Q&A that followed Aline’s presentation, she gave the following responses to the audience’s questions:

- A team should include a maximum of 20 people; a minimum of eight people. There should be at least two stations.

- On the first day, people on the Design Innovation Team led the stations; on the second day, product managers.

- Don’t evangelize your workshops just by talking. “Show what you can do”; how you helped teams to meet their numbers.

- “While many people don’t have good facilitation skills, many designers do.”

- To measure our success, we “established self-review questions that we asked right after a workshop, then two weeks later.” We used Net Promoter Score (NPS) metrics.

- “You want workshops to contribute to the quality of what comes out.”

- “We collected stories about what we’d done and documented them.”

- To get better at facilitation, “practice and get honest feedback. Assess each other as innovation catalysts by critiquing.”

- “When facilitating, push back to get people to leave behind their preconceptions and entrenched positions. When people hadn’t been working on a problem, this was easier than if they had.”

- “Design thinking is a way of approaching problems—the way designers think”—whether tackling tactical or strategic problems.

- “Breaking down barriers hurts.”

- “Lean UX focuses on work that gets done. Workshops broaden perceptions of the role designers can play.”

The Marriage of Corporate Strategy and UX Strategy: A Case Study

Reviewer: Pabini Gabriel-Petit

Presenter: Leah Buley

Leah Buley, shown in Figure 10, is a Design Strategist at Intuit. She gave a very fast-paced, high-energy talk on her experiences at Intuit, where she’s responsible for design strategy for small-business and personal-finance applications. Leah told us: “Intuit’s mission is to improve people’s financial lives.”

“Intuit has an interesting ambition: to be an innovative, growth company,” Leah said. The company has a 10%-time policy, which allows employees to devote 10% of their time to innovation. They can spend this time on whatever they think is interesting. Intuit uses Horizon Planning to think about its product strategy, using three innovation horizons:

- Horizon 1—incremental innovations that serve existing markets

- Horizon 2—innovating next-generation products that serve existing or adjacent markets

- Horizon 3—breakthrough, or disruptive, innovations that create new markets. Leah described the need for Horizon 3 innovations—experimental products that haven’t yet proven their viability in the marketplace—to focus on “love metrics” rather than monetary or other traditional metrics.

Innovation initiatives at Intuit include D4D (Design for Delight) and IAT (Innovation and Advanced Technology). D4D focuses on design and design strategy. IAT is a centralized group whose mission, according to Leah, is to “accelerate Intuit’s journey to be a premier innovative-growth company through game-changing design, technology, and new ways to work.” IAT sponsors two types of innovation projects:

- partnering with business units on complex, legacy products

- reimagining the future of their core products

Leah surveyed some of Intuit’s recent product innovations and their impacts on people. Then, she described how, in cognitive science, anchoring biases people toward their recent impressions, so familiarity with existing products anchors them. Intuit wants to put new anchors in place—aspirational anchors; not create incremental improvements, but disruptions. Leah shared this definition of strategy:

strategy (noun): an adaptation that serves an important function in achieving evolutionary success

Intuit partnered with IDEO in assessing its business goals, asking, “Who is our customer? Us→Business Unit→End User. Who in the business would be most impacted by the project? Who are our core partners?” “Surprise! It’s corporate strategy,” exclaimed Leah. “In parallel, we were working on the same goal: how to increase revenue from payments by envisioning the customer experience in five years. The CEO sponsored the Corporate Strategy effort with the goal of tripling revenues. The business units sponsored UX Strategy.”

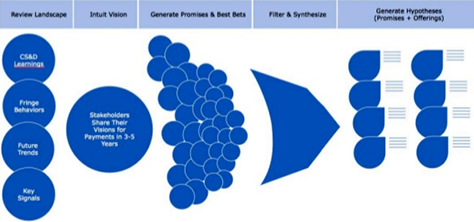

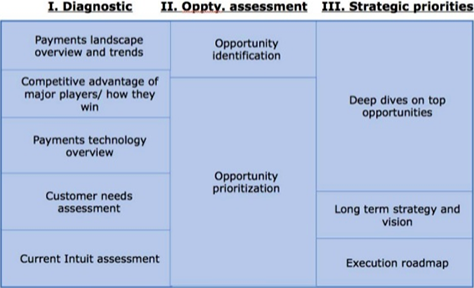

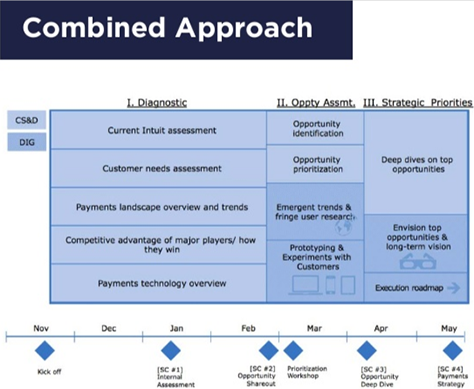

Leah contrasted UX Strategy’s “generative approach,” which Figure 11 shows, with Corporate Strategy’s “reductive approach,” shown in Figure 12. The focus of UX Strategy was on generating multiple hypotheses and product concepts. But the way Corporate Strategy approached project work was very different. They more quickly identified a small set of opportunities where Intuit would have competitive advantage, then did deep dives on them. The two teams were planning to do a lot of the same things, and leadership thought it was imperative that they work together. “Business has better business-intelligence data, but we kill it when it comes to understanding the user,” said Leah. While Intuit’s first attempt to unify the two different approaches “wasn’t very unified,” they finally came up with the combined approach shown in Figure 13.

To enable the two teams to work in concert on the project, they established the following "Terms of Engagement:

- Run as separate teams

- Appoint a liaison

- Weekly team meetings

- Share material back and forth

- Involve each other in key sessions”

They also assessed what things Corporate Strategy is good at versus what UX Strategy is good at, as summarized in Figure 14, and each team focused on what it did best. “Corporate Strategy is really great at understanding the competitive landscape,” said Leah. “They have great models for understanding the overall market and spotting market opportunities. They look at case-study analyses for predictive planning. They can answer questions like How long does it take to achieve what we say we want to achieve. In a sense, Corporate Strategy thus created the guardrails of the area for UX Strategy to play within. UX strategy’s strengths are seeing into people’s lives, trendspotting what is happening design-wise now—interaction paradigms, brand experiences, aesthetics—envisioning and validating new experiences and bringing them to life, and identifying customer insights.” Corporate Strategy looks at how Intuit is going to make money in the future; UX Strategy, what the money-making products of the future will look like.

As a consequence of working with Corporate Strategy and sitting in on its meetings, UX Strategy finally gained access to the CEO and got a seat at the corporate-leadership table.

UX Strategy gained interesting insights by doing iterative research probes, unfocus groups, and field research, then communicated the customer insights, design principles, and experience opportunities that they had identified. They created paper prototypes, then held an internal “science fair” where people provided feedback on them. The print deliverables that they created had very high production values. These included a concept cookbook that comprised an opportunity framework, five concepts, and notional product ideas; and small flipbooks, showing their design concepts. They created a walk-through exhibit for senior leaders, showing how the company would make three times as much money from payments. They created vision videos on product strategy. Finally, they led a roadmapping session, and the company adopted three core points of their UX strategy, which led to a corporate reorganization.

Leah concluded her talk by outlining the lessons UX Strategy learned from their experience “partnering with Corporate Strategy:

- You stand for the customer

- Look to their data for focus

- Be a friendly gadfly

- Make it vivid and sensory”

UX Strategy brought knowledge of the customer to the project and leaned heavily on Corporate Strategy’s rich business data. Together, they achieved success through building relationships and creating synergies between the two teams.

Clearly, user experience and innovation are important to Intuit, and they invest heavily in both. Intuit provides a shining example of what great companies that truly get the value user experience can accomplish and has a culture that many UX professionals would envy.

This was one of my favorite talks at UX STRAT 2013. Take a look at Leah’s beautifully designed presentation, shown in Figure 15. The UX Strategy team’s exquisite deliverables that her presentation depicts are especially interesting.

UX STRAT 2013: Leah Buley, “The Marriage of Corporate & UX Strategy” on SlideShare

Here are some of Leah’s responses to the audience during the Q&A that followed her engaging presentation:

- When someone asked about the timeline for the collaboration between UX Strategy and Corporate Strategy, Leah told us the project took place over seven months. After taking four months to discover their corporate strategy, it took two months for the company to realign behind it.

- The internal UX Strategy team comprised Leah and a Research Lead.

- Working with IDEO was really expensive—$500K for four people.

- Regardless of the size of a team, “it’s all about relationships and building trust; senior people having the conversations they need to have. In a smaller organization, figure out who makes corporate strategy decisions and who advocates for user experience.”

- “Definitions of the customer across UX Strategy and the business were a source of tension early on.” Corporate Strategy did not initially trust what UX Strategy thought were legitimate customers, so they took their framing from Corporate Strategy.

- Through user research, they needed to find people who could tell them what the future was going to be.

Redesigning Business Culture and Thinking Around the Customer

Reviewer: Margie Coles

Presenter: Tim Loo

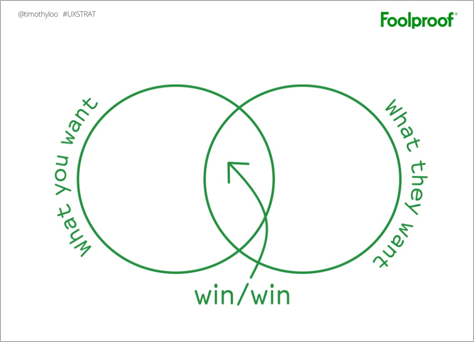

For those of us who missed Tim Loo’s workshop on Monday, it was great to have an opportunity to hear him speak Tuesday morning. Tim Loo, shown in Figure 16, is Strategy Director at Foolproof, a UK experience design firm that focuses on finding “the most valuable solution between what clients want and what customers want from each other: the win/win.” In this impressive, though brief, 30-minute presentation, Tim managed to be both entertaining and instructively insightful.

What is business culture, and why should we care? Tim defined culture for us, as follows: “Culture tells us how to behave when no one is telling us exactly what to do—it’s part coordination and part conscience. It determines how people interact with each other, including customers and stakeholders.”

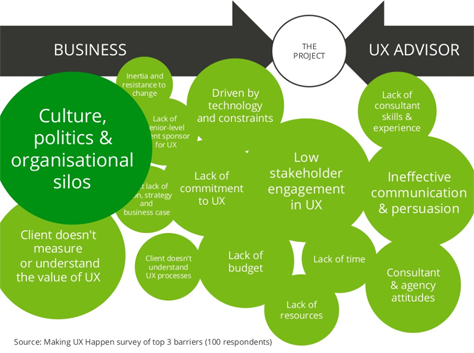

And why should we be interested in culture? To illustrate, Tim showed us the results of a survey in which he asked 100 UX leaders in the UK for the top three things that stopped them from being effective. Their collective answer: culture, politics, and organizational silos. Thus, culture is the primary barrier to creating and achieving great user experiences. Figure 17 shows a broader spectrum of the responses from this survey. We need to care about culture because it is either the primary enabler or barrier to delivering great user experiences. In one of the most tweeted quotes from the conference, Tim concluded, “Culture eats strategy for lunch.”

So, what type of culture is characteristic of big companies? Business leaders might say, “Our purpose is to make money.” Many big companies have become insular and narrow minded. Typical goals of IT- or Engineering-driven companies are to minimize costs or suppress change. This has spawned process-driven systems at the expense of innovation—as well as us-versus-them silos. The attitude that “for me to win, you have to lose” abounds. Many UX professionals conclude that it’s “me versus the matrix.”

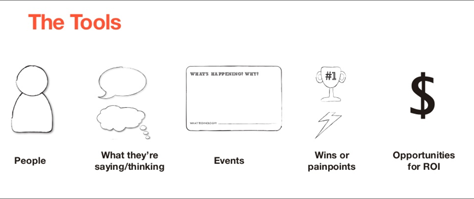

But just as changing one’s personality is possible, though incredibly difficult, and turning a large ship takes time, big companies resist change and change slowly. They aren’t organized in a way that naturally enables them to deliver great user experiences, and culture change is hard. The best way to effect change in a business culture, explained Tim, is to reverse the way in which we tend to view influencing relationships—from changing thinking to changing behaviors, as shown in Figure 18.

Tim proposes that, to change a corporate culture, we should purposely focus on affecting four business behaviors. At Foolproof, UX strategy means striving to make these four statements about behavior a reality.

- “We can all visualize what it’s like to be a customer dealing with us today.”—This is especially true for a large company. Create visuals showing all channels and painpoints, highlighting customers’ cumulative experience of chaos. Creating easily consumable stories or videos are highly successful means of capturing and communicating customer impacts on an emotional level.

- “We know and regularly communicate what [a] good experience looks like.”—Since most organizations can’t tell you what a good experience might be, you can help to articulate an operational definition of good, or what it means to customers for the company to live up to its brand promise. Create stories that show what will happen to customers when the company lives up to its principles.

- “We physically get together to make hard decisions and [make] trade-offs to deliver the right experience.”—Force people to get in same room. Companies often try to do too many things and must make trade-offs, choosing what they will and won’t do. Face-to-face collaboration is key to building empathy between colleagues, as well as with customers.

- “We measure and report on things [that] are meaningful for us and the customer.”—Before making any changes, measure how the customers feel about things. Surveys can help here. Doing this helps stakeholders to care about numbers that link customer outcomes to value.

The underlying principle of UX strategy is finding a win/win solution at the intersection of what the business wants and what customers want, as shown in Figure 19, thereby ensuring the profitability of the business.

By encouraging stakeholders to collaborate, we can change behaviors tangibly. Behavioral changes will, in turn, drive changes in thinking. In Tim’s parting words, he offered this advice: “Some of us will need to take a central role in effecting cultural change.” Indeed! I’m on board.

Take a look at Tim’s fabulous presentation in Figure 20.

UX STRAT 2013: Tim Loo, “Redesigning Business Culture and Thinking Around the Customer” on SlideShare