ICQ used to be the most popular online communications tool in the world. Released in 1996, it succeeded in the marketplace, registering 100 million users by 2001. Year after year, ICQ’s feature set grew—to the point where the company had to offer a second product?, ?ICQ Lite, which included “only the most popular features of ICQ.” Their original instant messaging application had gotten so bloated with features that they had to release a simplified version of the product.

RealPlayer is another example of a product that had too many features. Initially, it was just a simple media player, but it ended up offering CD burning, audio recording, RealPlayer Music Store, and more. In 2006, PCWorld magazine included RealPlayer on its list of “The 25 Worst Tech Products of All Time.”![]()

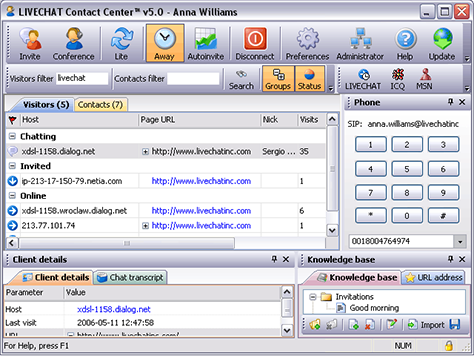

On the market since 2002, LiveChat, my company’s communications tool for Web site owners, had become bloated with too many features by 2006.

LiveChat let companies monitor traffic on their Web site, chat with site visitors, manage their business contacts list, integrate with ICQ/MSN instant messengers, and even make phone calls.

In the beginning, adding new features felt good. We loved employing new technologies, and our customers loved getting what they asked for. It seemed to be a classic win-win situation. We thought this was a good way to develop the product. This approach seemed logical to us: if we solve all the problems our customers have, we’ll finally create the perfect application.?

However, we reached a point where there was just no more room for new features. Adding another feature was no longer a 1-hour job. Where to place that new button? How to explain a new feature to customers? Our overloaded product was also much harder to maintain. A small change in one place could easily cause a bug somewhere else.

Along with the product’s new features, its number of use cases grew exponentially. We were surprised by some of the ways in which people used our product. For example, we provided agent-to-agent chats, so agents could help each other while serving challenging customers. As it turned out, some of our clients were using that feature to collect pizza orders in their company. These customers didn’t really need to use our product for that. They might easily have used Skype instead.

Escaping from the Trap

In 2009, we took a step back and finally understood that feature overload is not a good way to go. We made a decision to simplify the product as much as possible.

At first, we had planned just to cut features from our existing product, but came to feel that this would amount to simply painting the grass green. Making small, iterative changes would change only the product’s appearance. Instead, we wanted to improve the whole user experience of our product, so we decided to create a new version of our application from scratch.

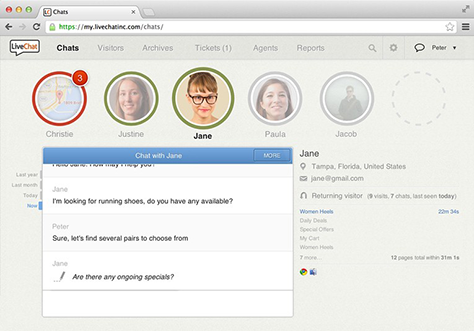

After eleven months of hard work, we released our new application and a new product Web site. We also provided our customers with lots of high-quality materials that helped them to better understand the product. The results were satisfying. After just six months on the market, our new product was getting 20% more customers a month. After a year, 70% of our customers had decided to migrate to the new product.![]()

Our new customers were spreading the word about our application’s great user experience. One said, “I’m loving everything about #livechat. You guys have a beautiful user experience.”

Lesson Learned: Product Teams Should Learn to Say No

During our product redesign process, I learned how important it is to manage feature requests from customers properly. Customers really wanted to be helpful and bring value to the product. Even though customers’ specific use cases biased their requests, it’s natural that others would have the same problems. This might seem to be definitive proof that making the decision “Let’s build that!” was the right way to go. However, this would have been a short-sighted perspective. Do not rush to build something new just because of a single tweet or email message.

Having a clear vision that steers the design process brings value in the long run. It keeps your product clean, easy-to-use, and worth recommending. The problem is: people are more comfortable with making short-term decisions. A good product manager must always keep a product’s long-term vision in mind.

Being this disciplined is especially hard for developers. Blindly following the path of building more new features is the way they’ve typically worked. Getting a task, completing it, and moving forward feels good. By nature, developers love building things, so the idea of removing features feels like a step backward.