Basing the Service Proposition on Insights

The service proposition is essentially the business proposition, but seen from both the business and the customer/user perspective. It is important that some kind of business model lies behind the service—even if it is a free or public service—otherwise it will not be sustainable or resilient to change. The usual approaches and questions apply: Who is going to fund it? What is the price point and market segment? What do we need to deliver the service, and what will it cost?

The service proposition needs to be based on real insights garnered from the research. For example, is there an unmet need, a gap in the market, an underdeveloped market, a new technology that disrupts existing models, an overly complicated service infrastructure that can be radically simplified, or a changing environment? Any one of these might lead to a business idea and, in turn, a service proposition.

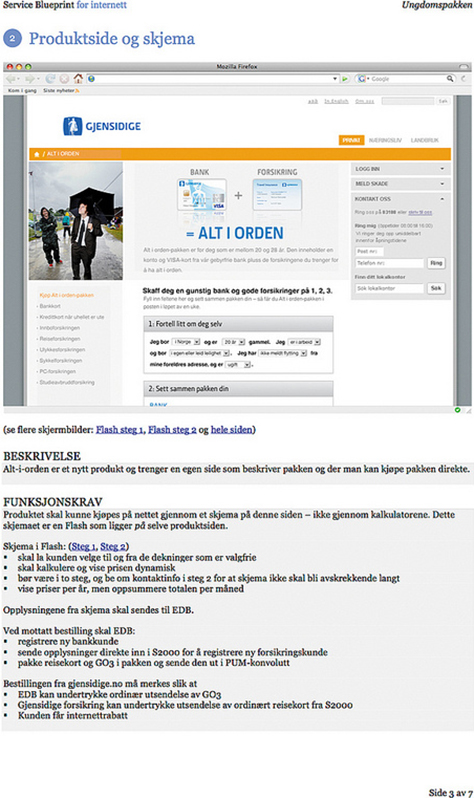

The Zopa Service Proposition

Peer-to-peer lending service Zopa.com (Figure 1) is an excellent example of a service proposition based on the insight that companies have a very different relationship to financial services than individual consumers do. One reason for this difference has to do with the way companies are rated by third-party agencies (or the market), which enables companies to present themselves as a viable lending proposition to the financial industry. This system led to the development of the bond market, which allows financial institutions to invest in companies while spreading their risk. This, in turn, allows companies to borrow money in ways not available to consumers, and usually to get a better deal. The Zopa co-founders saw the opportunity to create a similar “bond market” for individuals. A person who may not want to lend L1,000 to one person might be willing to lend L1,000 to be divided among 100 people because the chances of default on the entire amount are very low.

Zopa is also a good example of insight into the power of networks and data as the fuel for disruptive innovation. Behind the scenes, Zopa’s proposition is the insight that the data needed to create such a rating system on individuals are out there, but as Zopa co-founder Giles Andrews explained, “Banks have done a fantastic job of telling everyone that they own all this data, which they don’t, of course. It’s yours, it’s mine, it’s everybody else’s. It certainly doesn’t belong to banks, but the industry is structured in such a way that it became very difficult to get that data.” (See Giles Andrews’s IPA talk.![]() )

)

Although individuals can apply to credit rating agencies to get the data held on them, they cannot do much with it. Zopa helps empower individuals by using this data to rate their creditworthiness in a peer-to-peer lending market. Zopa’s service proposition is that both lenders and borrowers can get better rates than they would from banks. (Zopa stands for Zone of Possible Agreement—the overlap between what a person is willing to sell for and another is willing to pay.) To do this, Zopa needed to translate their financial thinking into a compelling service and social experience that people could understand and would want to use.

In fact, another opportunity insight for Zopa was the increasing social use of the Internet and the fact that by 2004, when the Zopa founders were starting up, eBay was the biggest online marketplace in the world. Zopa’s founders could not explain eBay in any rational economic way. After all, people seemed willing to take the risk of sending money to complete strangers with almost no security, something that a bank would never do. The only way they could explain it was in terms of eBay as a social experience in which people and personal reputations matter.

Zopa is a good example of an organization starting at the people end of the process, asking “What can we do for individuals who do not trust their banks, and how can we build a service business around that?” This is why service design takes a bottom-up, needs-based approach to designing services with people.

Returning to the development of the service proposition, it is important when sketching out the ideas at this early stage that the following three questions can be answered:

- Do people understand what the new service is or does?

- Do people see the value of it in their life?

- Do people understand how to use it?

We will revisit these questions in Chapter 7, and add some more as well, but for now let’s take a look at these three in turn.

Do People Understand What the New Service Is or Does?

This question may seem obvious, but unlike products, which have physical affordances signaling their potential usage, services can be abstract or even invisible. New services often chart new territory, so explaining what peer-to- peer lending is, to use Zopa as an example, is important. If people are used to borrowing money from banks, they might not understand the point of Zopa. Here is how it is explained on the Zopa website: “At Zopa, people who have spare money lend it directly to people who want to borrow. There are no banks in the middle, no huge overheads and no sneaky fees, meaning everyone gets better rates.”

So, now we have a pretty good idea of what the service does, but do people want it in their life?

Do People See the Value of It in Their Life?

Arguably, the biggest sin designers, engineers, and technologists commit is coming up with stuff they think is cool but nobody actually needs. History is littered with entirely useless products and services. History is also speckled with things people initially thought were useless but that turned out to be things we can hardly live without, such as text messaging, sticky notes, and websites with pictures of cats doing funny stuff.

If you are developing a service proposition, it is essential to think about how it adds value to people’s lives. This should, of course, be neatly based on the needs that you uncovered through the insights research, but projects also get steered from above within organizations. Watch out for service propositions that start veering more toward the needs of the business than the customers. The ideal is a proposition that is win-win for both service provider and service user, with each side providing value to the other.

This is how Zopa explained their value: “We hear you ask, ‘Why would anyone lend money to a complete stranger?’ Because, quite frankly, it gives a better return than saving with a bank. With over L160 [million] lent and a proven track record of managing your money better than banks, we think you should be asking, ‘Why not?’ ” (As of late 2012, the figure is now more than L230 million lent. Giles Andrews, personal communication, February 13, 2012.)

Many people feel that their bank is a necessary evil that is always trying to rip them off with spurious fees. For this reason, people feel little loyalty toward banks. Zopa confirmed this insight (a pretty obvious one, when you think about it) through their research. People do not trust banks to look after their best interests, but they do trust that their money will be locked up in a big vault somewhere, even if it is just a digital one.

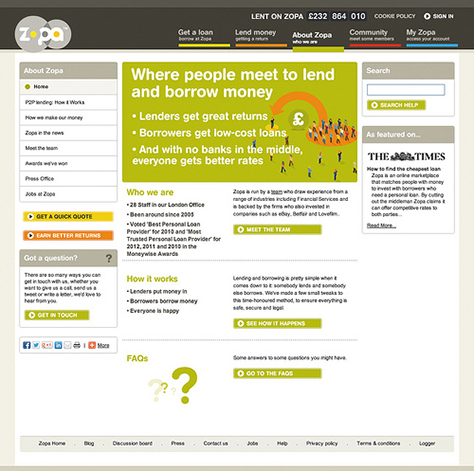

Zopa looked at how they, as a start-up, could compete against this love-hate relationship that customers have with banks. The result was to “go for the soft side of trust,” according to Giles. (Both Giles Andrews quotes in this paragraph are from his IPA talk.![]() ) They came up with a tone of voice that is both friendly and straightforward, sometimes funny but not flippant. This guided the design and communication of all their touchpoints: they are as clear and transparent as they can possibly be about how they make money, what the charges are, and what happens if things go wrong. This is the complete opposite of what banks typically do. As Giles explained, “[Banks] have huge amounts of small print. They make their money out of people making small mistakes and they don’t make their money out of providing a fair service most of the time.” Zopa also emphasized the human side of lending and borrowing money (Figure 2), something that many people feel banks have lost sight of.

) They came up with a tone of voice that is both friendly and straightforward, sometimes funny but not flippant. This guided the design and communication of all their touchpoints: they are as clear and transparent as they can possibly be about how they make money, what the charges are, and what happens if things go wrong. This is the complete opposite of what banks typically do. As Giles explained, “[Banks] have huge amounts of small print. They make their money out of people making small mistakes and they don’t make their money out of providing a fair service most of the time.” Zopa also emphasized the human side of lending and borrowing money (Figure 2), something that many people feel banks have lost sight of.

So, a combination of the service proposition’s underlying principles and how they are communicated across touchpoints helps people understand not only what the proposition is, but the value it has to them. The next thing to tackle is whether they understand how to use it in practice.

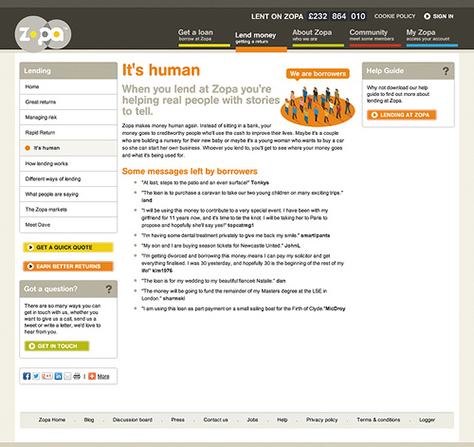

Do People Understand How to Use It?

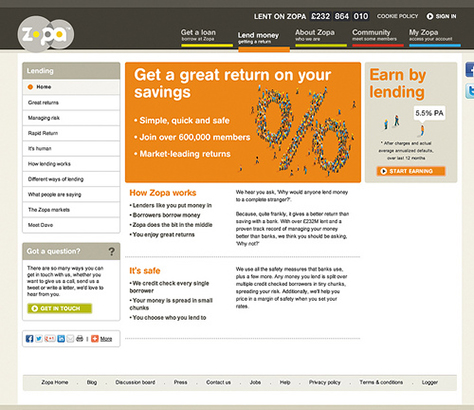

You may have been working on a new service for a while, and the client you are working for should certainly know their business, but do the potential service users understand it? We know how to use a door handle, for example, because we have grown up with them and door handles have physical affordances that encourage us to push, pull, or turn them, but a peer-to-peer thingamabob? Potential users need to have some idea of what “peer-to-peer lending” means, which is why Zopa explain their service as “a marketplace for money.” They also explain how their service works, which is more than most traditional banks bother to do (Figure 3).

So now we know what the service proposition is, understand the value of it in our lives, and have a rough idea of how it works and how to use it. Zopa is charting new territory, so they have spent a lot of time and effort detailing the “how it works” sections of their website to help people understand the service and build up trust in it, which is central to the business.

Other service propositions can benefit from metaphors and piggybacking on existing, well-understood products or services. For example, WhipCar is a peer-to-peer car-sharing service that allows people to rent out their own cars to strangers when not using them. Because Airbnb, a service that allows people to rent out a spare room, an apartment, or even a house to strangers in the same way, was already an established service (Figure 4), WhipCar can describe themselves as “the Airbnb of car sharing” and half the job is done for them (Figure 5). Obviously, people need to know about Airbnb first, but many of WhipCar’s early adopters were also early adopters of other collaborative consumption sharing services such as Airbnb, so the comparison was well targeted.