Why Is First Use Important?

The success of any product depends upon many things, but these three factors play pivotal roles:

- Potential customers must understand what you are selling and why it’s worth their time and money.

- Your customers must be able to get up and running quickly and easily.

- You must deliver sustained value if your business is going to last.

I know this is basic stuff, but these factors build upon each other: Miss #1 and you can’t get to #2—never mind having the good fortune to be in a position to deliver #3. That’s why I like to think of first use as the first time a potential customer encounters your business.

Consider these four tips when crafting your first-use experience:

- Be very clear about what it is that you are selling and why people would want it.

- Make it drop-dead easy to sign up—or better yet, make signup an integral part of first use.

- Incorporate step-by-step guidance, videos, and tips into the user interface.

- Do usability testing.

Tip 1: Be very clear about what it is that you are selling and why people would want it.

If, after looking at your Web site or marketing collateral for 5 to 10 seconds, a potential customer can’t repeat back to you what it is that you offer, there’s a problem. I often use Five Second Test![]() to try out various homepage designs. It’s easy to run a study: You upload some screenshots and add a couple of questions that you want to ask users. Each user has five seconds to review your page and answer the questions. Then you get a nice little report at the end. It’s cheap, and it’s low overhead. You could do it today.

to try out various homepage designs. It’s easy to run a study: You upload some screenshots and add a couple of questions that you want to ask users. Each user has five seconds to review your page and answer the questions. Then you get a nice little report at the end. It’s cheap, and it’s low overhead. You could do it today.

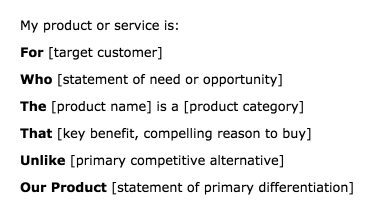

If you are still struggling with your design after a number of iterations, you might want to do the exercise shown in Figure 1, from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm.

Forget jargon-laden mission statements. Take just a few seconds to state these parameters clearly and concisely, and you’ll be in good shape.

Tip 2: Make it drop-dead easy to sign up—or better yet, make signup an integral part of first use.

The most engaging sign-up experiences are those during which users are actually getting something done, as opposed to doing busy work—that is, filling out a form. There are many great examples, but here are a couple that stand out for me: Mindmeister lets users try a live demo and actually create something, then sign up afterward. Letting people use your product first is an effective strategy because, once users have invested their time, they can see your product’s value, and you’ve pretty much got them hooked. The same goes for Gliffy, where users start by creating a diagram. Only when they click Save does the site request their sign-up information.

There are some good resources that provide guidelines you can follow when creating your sign-up form. I recommend your reading Luke Wroblewski’s Web Form Design: Filling in the Blanks. It’s a quick and easy read, and you’ll get practical advice for improving your sign-up form.

One guideline that I’d like to stress: please don’t ask for any information you don’t really need. The goal is to close the deal, not gather demographic information. You can ask for that later if you really must.

Another piece of advice I’d like to offer relates to the layout of your sign-up form: If there are only a few fields—which means you have a nice, concise form, way to go!—place labels above the fields instead of at their left. This is cleaner visually, and users can easily scan the form. Placing labels within fields is becoming more prevalent and may work okay if a sign-up form is very short and the label/value pairs are familiar—as for name, email address, and password. However, because a field’s label disappears once a user clicks the field and the field is in focus, I advise against taking this approach for longer forms.

Finally, your email confirmation message should do the following:

- Reassure users that they’ve been successful.

- Give users a place to go if they have questions.

- Give users a clear call to action—Get started now! or some such.