Designing in HTML is not the only issue. I have similar concerns regarding almost any specialized tool or solution for UX design—like doing all design work in Axure or Fireworks.

I actually think we need many tools and should use the best tool we can for any one design or communication task. I also have some concerns about how bad tool choices can cause breakpoints between design phases, so can result in concept ideas getting lost if a designer switches too vigorously from one style of work to another. But that’s a discussion for another day.

In this column, I’ve put together a discussion of a few of the tools and design practices that I regularly use.

Creating UI Specifications

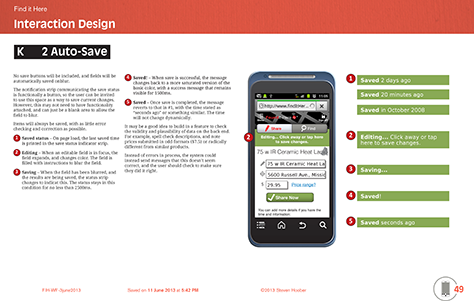

I suppose I could have called this wireframing, but I have issues with the use of that term. Not because I disagree in any significant way with any of the principles of wireframing, but because the term is sometimes misapplied or misunderstood to mean only drawings. With a wireframe mindset, annotations are too often a nice-to-have feature that gets tacked on later, if at all. Simply calling a design document a specification helps a lot. For me, this means that about half of any page in the specification is filled with words—like the whole left side of the specification page shown in Figure 1.

My focus on writing enough to call what I create a specification also drives the tools that I use for creating design documentation. Lately, I’ve been drawing in OmniGraffle and Visio, and I have tried several other tools over the years. But these days, when I have a choice, I draw in Adobe InDesign. It has most of the features of Illustrator, but better supports the creation of multi-page documents, so makes it easier to create complete documents. Plus, it provides superlative text creation, editing, and formatting tools. It even supports index creation and has GREP for really complex search-and-replace tasks if that’s what you need.

I know lots of people who like other tools for their many existing templates. But I have a design background, and I like to work with people who can also draw. I prefer having the flexibility of a fairly full-featured drawing tool, so I can come up with all-new solutions to problems and, if necessary, shift the degree of fidelity with which I’m representing any design. When I’m working with a separate visual design team, I draw in gray scale or lines, but when I am the sole designer, I tend to skip doing user interface design as a separate step, so simply draw high-fidelity mockups in my interaction design and architecture documents.

Communicating Concepts

Another key task in which I employ my ability to draw almost anything is in communicating concepts, choosing whatever way is most relevant. Concept documents of various sorts—some of which I’ve shown in Figure 2—are crucial to communicating initial ideas and making sure everyone is working off the same page.

Whether you write about or draw mobile UX design concepts, you should communicate details about services, data, sensors, networks, and users. Maybe provide flow charts. Hardly ever screens. Storyboards and other ways of organically showing key principles relating to users’ tasks are great. So much so that I regularly have to repurpose such documents for use in presentations and slideshow decks that go out to executives and venture capitalists. As much as a demo or prototype can add value by explaining what a product is and how it works, it is important to set the context and explain your future plans.

Creating Scalable Designs

The other key reason that I use a vector tool—usually InDesign—over anything raster- or pixel-centric is that I stick strongly to principles of multi-device design, so I never like to get locked into one scale. Vector drawings can easily be adapted to other scales and let you show several user interfaces at once with minimal effort.

More importantly, this sort of work process rapidly leads you to assume that everything can stretch or shrink, so you’ll draw and specify in percentages, ratios, physical sizes, or other ways that work on every device. It helps you not to be so worried about the fragmentation of your platform, even when talking to developers about implementing your design work.

Using Pencil, Paper, and Hardware

Drawing on paper is a great tool. I don’t do this for every project, but it’s a capability that is always available to me. My briefcase always contains a drawing pad, markers, pencils, erasers, rulers, and a Touch Template. But I don’t usually use pencils. Instead, I use marker paper and a gray marker for layout, then draw details in other colors.

Sometimes, drawing on paper is the best way to do group work. Even if you’re the only one drawing, it can be more engaging for a small group. Plus, I travel a lot, and drawing on paper is also great for airplanes and other environments where drawing on a computer doesn’t work so well.

I know of people who do pretty much the same things on their iPad. But that doesn’t work well for me. I like tools and physical media.

Designing and Reviewing at Device Scale

A key to designing for mobile devices especially is to design at device scale, as shown in Figure 4. I do this as much as possible regardless of how I am drawing. It’s important to get everyone to think at device scale and in the device context. Even if you present your designs on a big conference-room screen, try to pass around either paper printouts that show the screens at their real size or some sample devices displaying the screens.

One of my favorite things to do is to put designs—whether scanned sketches, wireframes, or comps—onto a mobile device. Just looking at the interfaces in the device’s photo viewer or gallery can really pull people into the right mindset. This works so well that I’ve done pretty good first-run usability tests like this

For paper sketching, I have prepared some device templates that I print out to make it easier to keep the various devices in mind. Making several templates available—rather than printing out only an iPhone template, for example—also helps to remind everyone about what happens when you switch devices or orientations or how to design for phones and tablets at the same time. If you’d like to use some of these templates, you can download a printable PDFPDF![]() or an editable InDesign CS6 file.

or an editable InDesign CS6 file.![]()

If all that’s not crazy enough, I sometimes even use plywood tablets, eReaders, or mobile devices on which I sketch or tape designs. If you don’t have the woodworking skills, just get your scissors out and tape bits of paper to your actual phone. It works surprisingly well. But of course, there are commercially available templates, sketchpads, and other products that can help with this if you want to buy them.