In this article, I’ll first look at how people move through such information environments—the behavior of wayfinding. Then I’ll outline a set of guidelines for building Web sites and applications that enable people to make sense of continually expanding volumes of information without their becoming overwhelmed.

Wayfinding Behavior

Information wayfinding provides a valuable lens for viewing people’s interactions with information. The term wayfinding refers to the cognitive process of spatial problem solving that people use to navigate physical environments. [1] Information wayfinding, then, is the collection of cognitive processes that people use to navigate information environments. People most often exhibit information-wayfinding behavior in one of three different modes: locate, explore, and meander.

Locate

People operate in the locate mode of wayfinding when they know precisely what they’re looking for, but need help discovering where to look. Queries that are characteristic of the locate mode are sometimes called lookup queries. There is typically one right answer to a question. A few examples of people’s needs to locate information might be:

- Who was the director of the film The Third Man?

- What is the population of London?

- When are expense filings due?

- Where is Jimmy’s Pizza?

Explore

Exploring is much more open-ended than locating is. When people explore, the journey is as important as getting to the destination. As people encounter new information, their information needs evolve, making exploring an iterative, on-going process.

Marcia Bates has described this process as berrypicking—in which people move from one source to another, picking up nuggets of information along the way, as shown in Figure 2. [2] Peter Pirolli and Stuart Card describe the process as information foraging, in which people follow information scent along the way. [3] Both of these models depict information seeking in spatial terms and, thus, reinforce the concept of information wayfinding.

People might initiate exploratory wayfinding by asking questions such as:

- What kind of car should I buy?

- Where should I go on holiday?

- What film should I watch this evening?

Meander

While a particular information need prompts both locating and exploring, there is a third category of wayfinding that does not start with asking a specific question: meandering. People aren’t always looking for something in particular. They may have other motives such as having fun or killing time. [4] Checking your email or social networks while waiting for your bus to arrive are examples of meandering behavior.

These three modes of wayfinding—locate, explore, and meander—are not new concepts; they draw from the work of Gary Marchionini, [5] David Elsweiler, [4] and others. But they come to life and gain new meaning when we consider them in the context of information wayfinding.

Guidelines for Optimizing Wayfinding

Once we start thinking of information as an environment and wayfinding as the means by which people interact with that environment, the obvious next question is: How can I apply these ideas to the information environments that I create? There are six principles that should guide the way we construct information environments:

- structured districts

- flexible layers

- positional cues

- survey knowledge

- clear paths

- coherent interactions

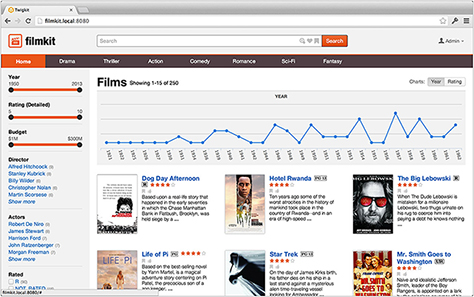

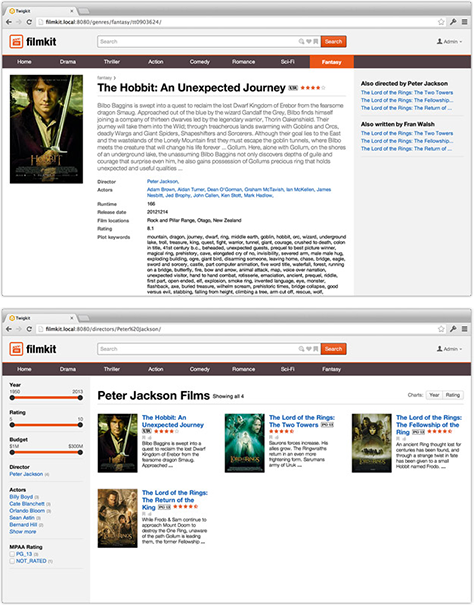

To make each of these principles more tangible, I’ve built an example using the Twigkit![]() search application framework, which I’ve played a part in creating, and the Google Search Appliance. (I even recorded a 5-minute video of its making that you can watch on Vimeo.

search application framework, which I’ve played a part in creating, and the Google Search Appliance. (I even recorded a 5-minute video of its making that you can watch on Vimeo.![]() ) This example uses a collection of films to demonstrate what an information-wayfinding experience could look like.

) This example uses a collection of films to demonstrate what an information-wayfinding experience could look like.

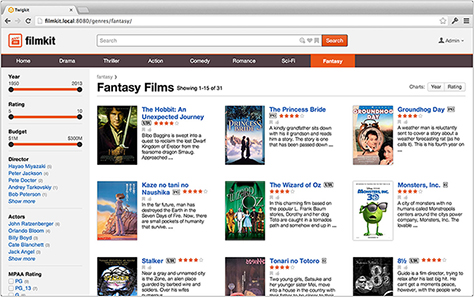

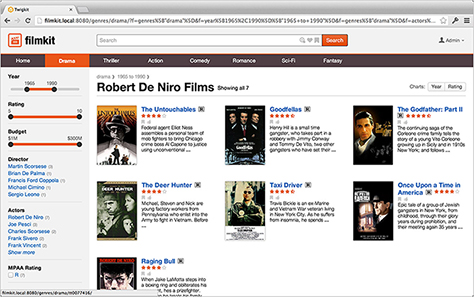

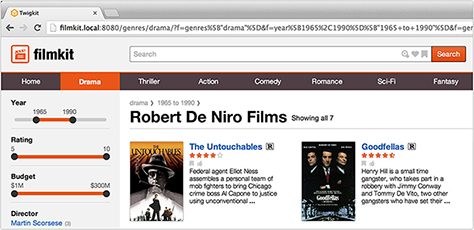

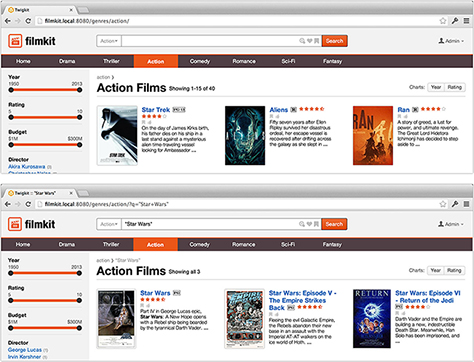

1. Structured Districts

Structured districts are the main categories into which we can divide an environment. Logical, clear districts are important to helping users understand an information environment at its most basic level. Districts should correspond to the user’s own mental model. When people think about films, for instance, they think in terms in genres—for example, an action film, a drama, a comedy, or a thriller. Virtually every information domain has some dominant organizational scheme that should form the districts of its information environment.

It’s essential to clearly present districts to users—perhaps in a form that resembles traditional Web navigation systems. Likewise, we should also base URL schemes on districts. In the example shown in Figure 3, genre is the source of the districts that drive both the primary navigation and the URL structure.