A Brief History of the Pile-Sort Method

Michael Burton [1] first introduced the pile-sort method to anthropology in 1975 as a method of collecting data about “what goes with what.” In his study, Burton asked 108 high-school students to group the names of 58 American-English terms for roles in whatever groups they felt belong together. The same study later introduced factor analysis to create a mental map of role associations the study participants made. In the social sciences, pile sorting and factor analysis have since become a common combination of research methods for exploring people’s mental maps of the terms used within a particular cultural domain.

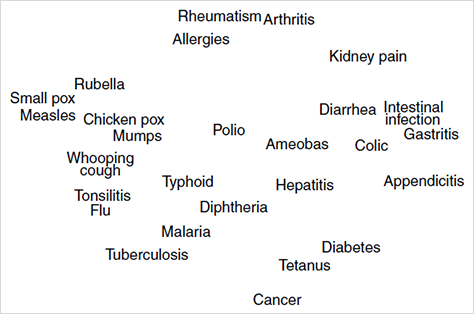

Here is one example of the usage pile sorting and factor analysis in anthropological research. Susan Weller [2] asked 20 urban, Guatemalan women to list all of the illnesses they could think of. Subsequently, she compiled a list of the 27 illnesses they named most frequently, put each of them on a card, and asked 24 other women to sort the cards into piles according to similarity. Figure 1 shows the factor-analysis results for Weller’s pile-sort data, using a multidimensional scaling (MDS) graph. The graph visually plots the illnesses that the study participants regarded as similar. For example, there is a clump of gastrointestinal disorders in the upper-right corner and a clump of childhood disorders in the upper-left corner.

Source: Susan C. Weller. “New Data on Intracultural Variability: The Hot-Cold Concept of Medicine and Illness.” Human Organization, Volume 42, Issue 3, 1983.

Determining User Task Flows and Contexts of Use

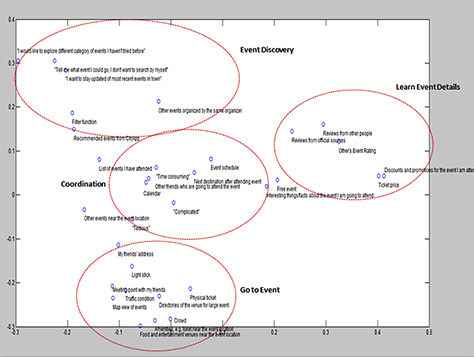

One common deliverable from user-research activities is the user task flow, which maps out a sequence of tasks that users need to perform using a product that a team is designing. Recently, while working on a mobile application for events, we encountered a situation in which the design team already had comprehensive knowledge about how people would prepare to attend an event. However, this information was scattered among individual team members and embedded in discrete artifacts. Team consensus was lacking. We decided to work with the design team to gather all of the available information, then use the pile-sort method to create a task flow comprising all of the steps that users would take in preparing to attend an event.

The design team was working in an agile environment. While preparing for the pile-sort study, the designers realized they needed to answer another, probably less straightforward question that was a matter of deep concern to them: “How will our product support users at each stage of their tasks?”

We believed that the answer to this question resided somewhere within the context in which the users were performing the tasks. While user context is a difficult term to define, for the purpose of our work, we considered context within the scope of the following questions:

- What other, concurrent tasks is the user performing?

- How does the surrounding environment permit or inhibit the performance of the user’s tasks?

- What kind and degree of sentiment do users attach to the various tasks?

We searched our toolbox for an appropriate tool that would complement the pile-sort method and help us to accomplish our task of understanding contexts of use, but did not manage to find one. We had sought inspiration from practices in anthropology—more specifically, from the area of cultural domain analysis, in which field researchers often need to discover the mental maps of people within particular cultural domains. This goal strongly resonated with ours, which was to discover contexts of product usage by mapping out the associations that users make between their tasks and the contexts of their surrounding environment.