In this third installment, I’ll explore the surprising mix of misperceptions, biases, and cognitive mechanisms underlying the decisions people make when facing ethical choices, which unfortunately encourage us to come up with juicy rationalizations for unethical decisions.

Not As Ethical As We Think

“People believe they will behave ethically in a given situation, but they don’t. They then believe they behaved ethically when they didn’t. It is no surprise, then, that most individuals erroneously believe they are more ethical than the majority of their peers.”—Ann E. Tenbrunsel, Kristina A. Diekman, Kimberly A. Wade-Benzoni, and Max H. Bazerman [2]

As in the mythical town where every child is above average, it is obviously impossible for everyone to be more ethical than his fellows. Surprisingly, however, consistent findings from psychology, management, sociology, and economics research show our ethical behavior is quite a bit worse than we imagine. We not only choose unethical options more often that we think when facing ethical dilemmas, but after the fact, we also change our ethical standards and our memories to justify the many unethical decisions we make. [2]

Considerable research on decision making and business ethics shows a powerful combination of cognitive distortions, shifting perceptions, and personal biases—a combination that recalls the dialogue about juicy rationalizations from “The Big Chill”—heavily affect the choices we make when faced with ethical dilemmas. To shed light on the mechanisms that affect our decisions, I will summarize some of the most relevant research, with an emphasis on how these findings relate to user experience design. It seems we all carry a bit of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Imp of the Perverse.”

Bounded Ethicality

Perhaps the most important thing to understand is that we do not consistently apply our own ethical standards. Instead, we place boundaries on how our morals apply, doing so “in systematic ways that favor self-serving perceptions.” [2] Bounded ethicality involves more than simply deciding when and where to apply ethical standards to our decisions. Researchers studying the subject find “people develop protective cognitions that regularly and unwittingly lead them to engage in behaviors that they would condemn upon further reflection or awareness.” Bounded ethicality helps explain how “an executive can make a decision that not only harms others, but is also inconsistent with his or her conscious beliefs and preferences.” [2]

Many ordinary self perceptions play a role in bounded ethicality, including the following:

- the desire to see ourselves as moral and competent despite contrary evidence

- ignorance of our own prejudices

- holding overly positive views of ourselves

- failure to recognize our own conflicts of interest

- unconscious discrimination that favors in-groups or people similar to us

Looking at the work of UX professionals, these perceptual biases appear in many forms such as the following:

- the assumption that we can speak for users without consulting them

- our conviction that our recommendations are inherently valid, even when uninformed

- placing greater weight on the views of people we happen to identify with

- believing our decisions always benefit users more than ourselves

Two Selves

Within the self-serving boundaries of our ethics, we listen to conflicting internal voices when we make decisions. Poe called this deep-seated desire to be contradictory the “Imp of the Perverse,” describing it as “an innate and primitive principle of human action, a paradoxical something, which we may call perverseness.” [3]

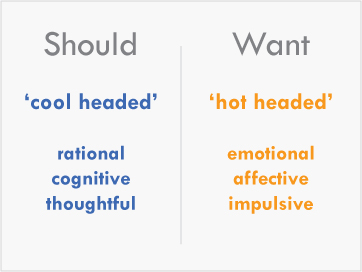

Ethics and psychology researchers call these competing perspectives the Want Self and the Should Self—though this is not to suggest we all literally harbor multiple distinct personalities. The Want Self “is reflected in choices that are emotional, affective, impulsive, and ‘hot headed’.” [2] In contrast, the Should Self is “rational, cognitive, thoughtful, and ‘cool headed’.” [2] Where the Should Self “encompasses ethical intentions and the belief that we should behave according to ethical principles,” the Want Self reflects actual behavior that is characterized more by self-interest and a relative disregard for ethical considerations.” [2]

Like the miniature angelic and devilish versions of the cartoon character Daffy Duck arguing over what course of action he should take, the presence of these two voices generates internal conflicts when we face decisions with ethical aspects. Their inevitable clashes can lead to some types of counter-intuitive behavior that are familiar to user experience professionals—such as making unreasonable design and delivery promises we cannot possibly meet or making misleading statements to persuade others or win business—sometimes called the Guru Effect.

The Three Phases of Decision Making

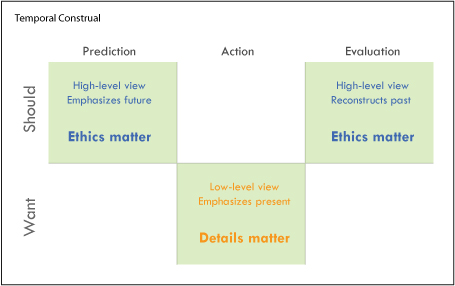

To understand how we make choices, psychologists divide our decision-making process into three phases called prediction, action, and evaluation. Prediction refers to the time before we act or make a decision, action occurs during the period when we act or make a decision, and evaluation occurs when we look back on our choices to assess them.

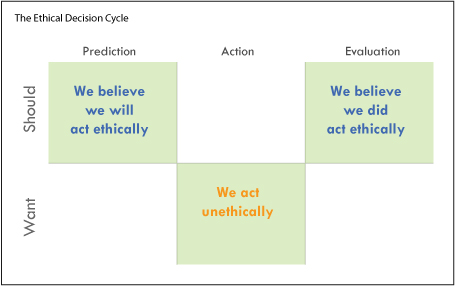

Based on their differing concerns and perceptions, our Want and Should Selves experience tension and trade control over our perceptions and actions at alternating stages of the decision cycle. During the prediction phase, our Should Self leads us to believe we will choose to act ethically, in a manner consistent with our beliefs. During the action phase, our Want Self dominates, and we behave unethically. Finally, in the evaluation phase, our Should Self retrospectively alters our perceptions of our behavior, crafting juicy rationalizations to bring our choice in line with our ethical beliefs. [2] Figure 2 illustrates this pattern.

This separation of our Want and Should Selves during the different stages of the decision cycle “allows us to falsely perceive that we act in accordance with our Should Self when we actually behave in line with our Want Self.” [2] Overcoming this separation across the timeline of decision making is the focus of most recommendations for improving our ethical choices.

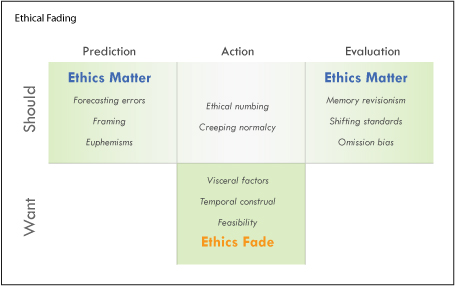

In addition to the tension between our Want and Should Selves, two other mechanisms come into play over the course of the decision cycle: ethical fading and cognitive distortions.