Content and Presenters: Highlights

Day 2: RIA Patterns: Best Practices for Common Patterns of Rich Interaction

Presenter: Bill Scott

Bill Scott (Figure 12) presented the great work Yahoo! has done on its Design Pattern Library (Figure 13), which represents the state of the art in rich, interactive Web applications and is freely available online. I’ve heard him present this material twice before. He very effectively evangelizes the mission at Yahoo! “Bring about sane design.” “The business reason behind open sourcing the pattern library,” Bill told us, “It’s good for PR, feedback, and clarity. … Patterns are great for forming a design vocabulary.”

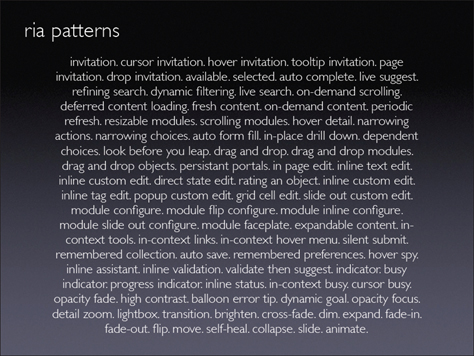

Figure 14 shows the evolving collection of RIA (Rich Internet Application) patterns Yahoo! has created.

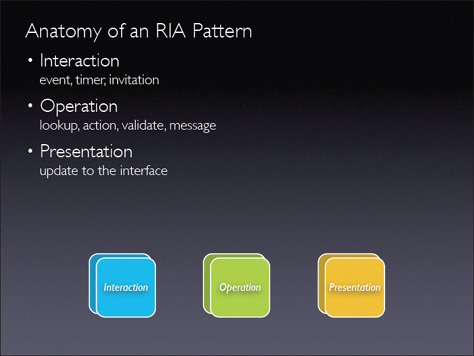

Bill said, “You can dissect a pattern into a framework,” as shown in Figure 15. According to Bill, “What’s changed with Ajax is: You can have a pipeline of just-in-time information delivery. How you manage the flow of information into a page is very important to keeping the user in the flow.”

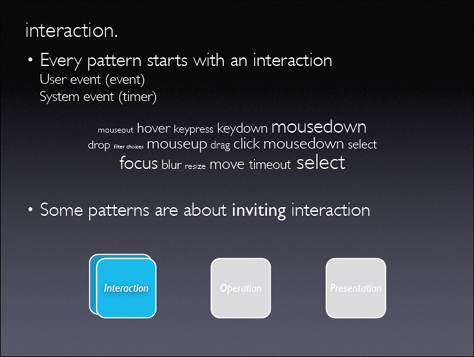

As Figure 16 shows, one example of a pattern is the invitation pattern, which lets a designer “cue the user that an interactive feature exists, because we have such a learnability issue on the Web." One type of invitation pattern is the hover invitation. With hover, “the user’s not safe to explore, because something’s always popping up on them. It comes up with hover, but the user must click a close box to close it. It’s extremely annoying to have something fly out at you when you’re moving the mouse around.”

There are two selection patterns: object selection and item selection. “As soon as you put selection into an application, you must be consistent. Use either object selection or item selection. If you mix those two things together, you cause problems, … especially with drag and drop.” said Bill. “With check boxes and drag and drop, there’s confusion in my selection model. … For selection models, the state of the art is pretty low right now.”

Another example of a pattern is the drag and drop pattern. “Interesting moments happen in a drag and drop interaction. Moving a ghost object should not move other things on the screen,” said Bill. To represent such interactions, Bill creates an “interesting moments grid, which is good for communicating fine-grained interactions to remote teams.”

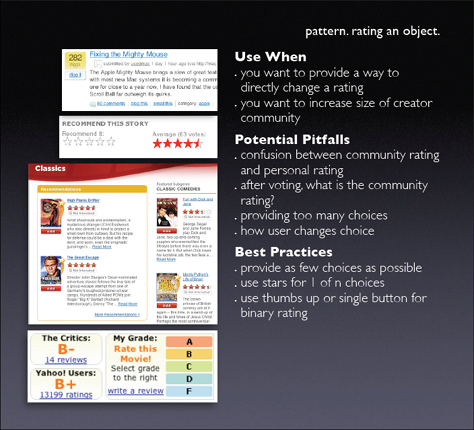

Figure 17 shows the rating an object pattern. Bill told us, ratings “made more people into creators.”

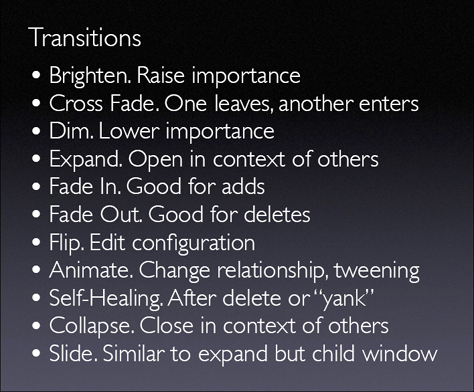

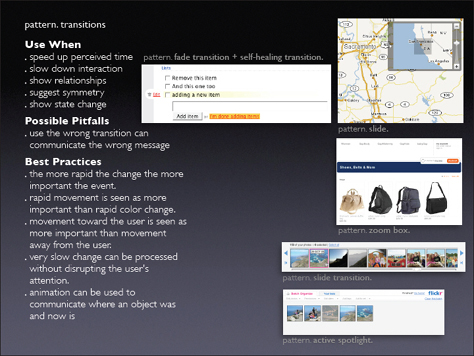

The transitions shown in Figure 18 “are all cinematic effects. With these techniques, you can slow down time, change states, redirect attention.” Figure 19 shows the transitions pattern.

Day 2: Communicating Concepts with Comics

Presenter: Kevin Cheng

I finally got to see Kevin Cheng’s (Figure 20) presentation on “Communicating Concepts with Comics” and really enjoyed it.

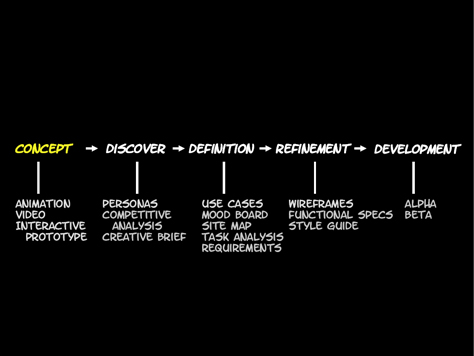

Rather than relying solely on the many more conventional design deliverables shown in Figure 21, Kevin uses comics to communicate “the core concepts behind a design’s intended user experience.” Most of these deliverables “focus on the interface instead of the user’s actual experience.” As Kevin said, “Comics are more expressive than words. A picture is worth a thousand words.” So, I’ll let Kevin’s images speak for themselves.

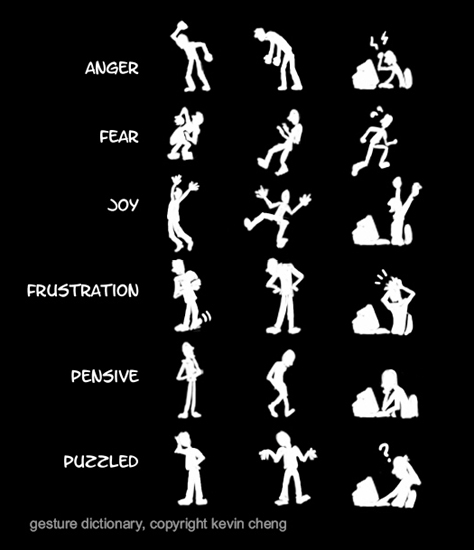

As shown in Figure 22, “Expressions bring more meaning to the words,” Kevin told us. “Body language does, too.” Figure 23 shows the emotions that various gestures communicate.

Comics can communicate motion and elapsed time. They let you “iterate rapidly and change things quickly,” said Kevin. “They connect at a very visceral level.” Figure 24 shows the broad palette of emotions you can express through comics.

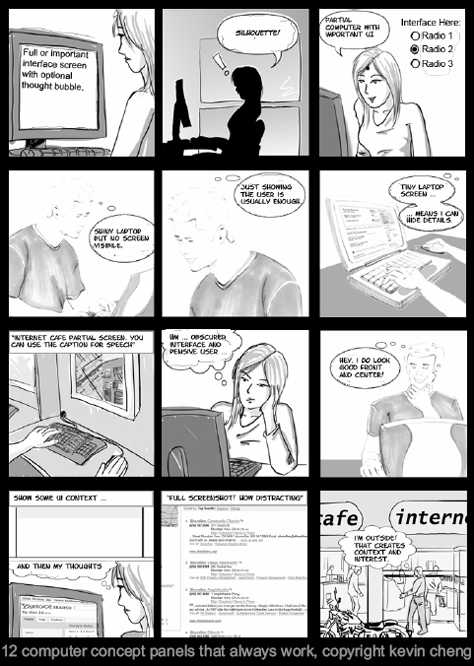

Figure 25 represents a variety of templates for panels in comics. Kevin told us, the panel in the upper-right corner “is the most useful. It’s the one I use the most. It just shows a bit of the user interface. I never show the whole screen, just a list or radio buttons. … You gain abstraction in using comics.”

“Comics are good for conceptualizing. They let you iterate and solicit feedback. Animation is better for pitching, or getting an idea across to management,” said Kevin. “The suggested length for comics: 10 to 12 panels are very easy to digest. Don’t put captions below them. Instead, use speech bubbles for words and thoughts. All dialogue should be within the comic. Right at the beginning, you’re focusing on the people you’re building for—the stories around them. One of the best things about comics is people will actually read them. They’re a great first step to get on the same page.”